Let’s get this out of the way:

*MOST OBVIOUS TRIGGER WARNING I WILL EVER GIVE*

Also, spoilers for a film from 2001.

54 Japanese schoolgirls walk through Ueno Station in Tokyo, laughing and smiling. As they wait for a train to arrive at the platform, they form a line and hold hands. On the count of three, they jump in front of a moving train, and gore ensues.

This is likely what most viewers remember about Suicide Club, if you were lucky enough to see it. Perhaps you came across a DVD copy rotting in a Hot Topic display above the comically-oversized belts. Perhaps a horror fan forced you sit through it. Regardless, this is a film that never received the kind of analytical attention it deserved, for a pretty wide variety of reasons.

Admittedly, while the opening is a memorable scene that expertly sets up the events to follow, it consistently overshadows the rest of the film. It’s a horrible shame, because what follows is a brooding, surreal cult classic full of existential dread and poignant social commentary. At least, I think so…

To really appreciate Suicide Club, you have to understand a little about Japan’s history with suicide. Most of us are probably familiar with the concept of Seppuku and/or Hara-Kiri. In feudal Japan, Seppuku was an honorable way of ending your own life in order to avoid the inevitable torture of captivity at the hands of the enemy, or to fulfill a death sentence. If you’re a Kurosawa fan, you’ve probably seen this on film hundreds of times, and it’s an iconic aspect of samurai culture.

In addition to being rooted in ancient tradition, Japan’s high suicide rate can be contributed to a variety of cultural norms and practices. For example, if you were to jump in front of a moving train in Japan, the train company could charge your family a fee. Banks are notoriously aggressive, and more often than not require a friend or relative to co-sign for a loan. This sounds like a fairly typical practice, but the Japanese tend to take this to the extreme, resulting in economic depression for many co-signers. By some allegations, banks even encourage debtors to take out life insurance policies on themselves, so they can end their own lives and pay their debt with the insurance money. Because of the shame that goes along with debt and failure in Japanese culture, taking out a loan is essentially putting your life (and the lives of your loved ones) on the line, and aggressive lending practices help create a cyclical pattern of monetarily-incentivized suicides.

Another contributing factor here is Japan’s responses to rectifying these issues. Mental illness is still very stigmatized and taboo, so when the Japanese roll out initiatives to decrease suicide rates, they’re usually tackling it from a purely socioeconomic perspective. Their question is, “How can we help individuals increase their standing in society?” rather than approaching this complex reality by asking, “How can we provide treatment for those who struggle with the shame and guilt brought on by unrealistic societal expectations, as well as various chemical imbalances that make these individuals more prone to suicide?” If you also consider that their culture values conformity to a group and one’s value to society over individual happiness, this affinity for suicide becomes significantly more plausible to a western perspective.

The romanticism of ending one’s own life is a factor here too, but even more disturbing is the sheer variety of words or concepts created to describe the various forms of suicide in Japan. Karoshi, for example, is suicide that results from being overworked, which is very common in the high-stress world of employment in Japan. Family suicide, which is not necessarily considered “murder” in the way we interpret that word, involves killing your own family before yourself, in order to spare them the shame and pain of living life as an orphan or widow. There is also the “lovers suicide,” a Romeo and Juliet-style reaction to the woes of forbidden love – something glorified in ancient Japanese theater since at least the 17th century. It should also be noted that the Japanese language naturally tends toward specificity, or rather that this is my impression. I’m not a Japanese expert, so interpret that how you will.

The particular kind of suicide this film addresses is shinjū, which literally translated means “double suicide.” However, after the rise of the internet, the term became more commonly used to refer to group suicide pacts formed by strangers on the internet. Adolescents in particular would meet each other on online BBS platforms (message boards) and plan their suicide method. They would then meet up in real life to carry out this plan. Immediately after the introduction of the internet, this became something of an epidemic in Japan, and it’s not very difficult to understand why in the context of such a culture.

Without this prior knowledge, Suicide Club is a thematic mess, and can almost come across as a celebration of suicide rather than an existentially-challenging satire. I’ll admit that what initially drew me to the film was the creative gore and surreal plot-line, but further analysis reveals a far more complex animal, with a clear agenda: to provide Japan with a much-needed wake-up call regarding the ways in which their societal norms contribute to this epidemic of low self-esteem and the trivialization of life. It is a film that approaches suicide from a western perspective, which is why it often comes across as trite. Most western cultures will already come from the perspective that suicide is a terrifying game in which nobody wins, but to the Japanese in 2001, this is socially relevant, and wrapping your mind around that can be difficult.

Suicide Club is directed by the notorious cult figure Sion Sono. His films tend to be subversive, and often have a completely preposterous premise. To give you an idea of just how “out there” this man is, here are some basic plot summaries from his filmography, pulled from IMDB.com, unedited for your amusement:

Love Exposure:

A bizarre love triangle forms between a young Catholic upskirt photographer, a misandric girl and a manipulative cultist.

Everyone is Psychic!: The Movie:

After receiving a cosmic blast while masturbating, a virginal teenager gains psychic powers and joins a group of ESP virgins in order to defend the world from evil psychics.

[DELIBERATELY NOT PICTURED]

Teachers of Sexual Play: Modeling Urns with the Female Body:

About a pottery workshop run by Ms. Namie. Her students want to become as skilled as her, and she teach them that the key to good pottery is love.

Into a Dream:

Low-profile theater troop actor Mutsugoro Suzuki begins an oneiric journey back to his hometown, marked by his quest to find the one responsible of infecting him with a STD.

Exte: Hair Extentions:

About hair extensions that attack the women that wear them.

Why Don’t You Play in Hell?:

A renegade film crew becomes embroiled with a yakuza clan feud.

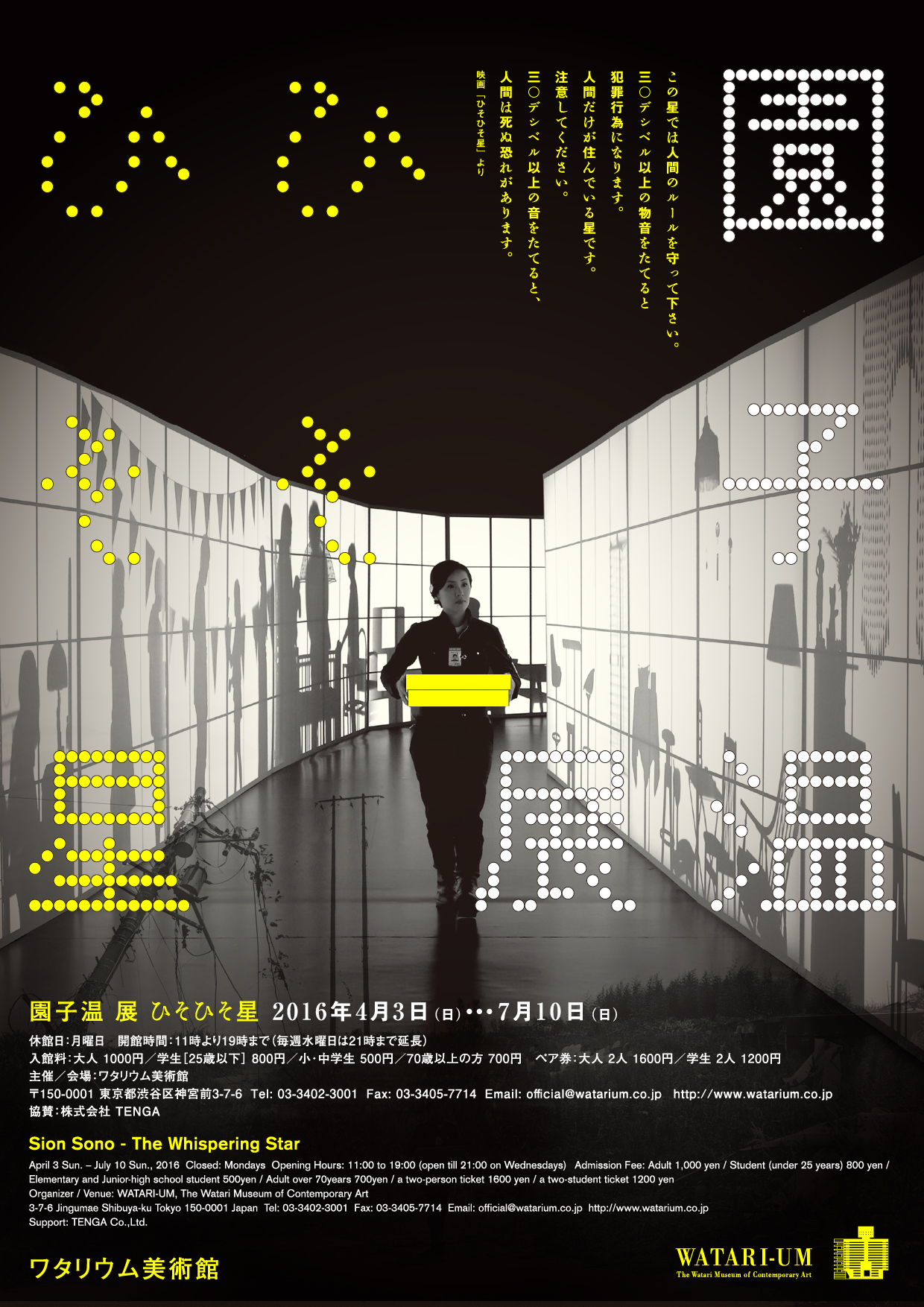

The Whispering Star:

A feminine android delivers packages to the scattered humans in the galaxy. With years to spare the android and us have time to contemplate what it is to be human.

The Bastard and the Beautiful World:

The Bastard and the Beautiful World is an omnibus film consisting of four episodes. (1) Fujiko is running as fast as she can, being chased after by a creepy masked man called Mad Dog. They meet a talented pianist on the way. (2) A mysterious relationship between a little girl, Utagui, who eats songs to live, and an artist who can’t sing anymore. (3) A married couple sets off on a journey to find the right arm of their dead son. They finally reached a beach in Okinawa and find…? (4) Bastards comes together on a night dance floor for a show.

Sono’s work is often so silly on a surface level that he practically dares his audience to take him seriously, and yet, aside from his adaptations and yakuza-themed films, he typically displays great depth. Even Exte: Hair Extensions, with its send-up of traditional Japanese ghost stories in which the antagonist is almost always a female with long black hair, tackles themes of parental abuse amidst the over-the-top violence. That’s not something you expect to hear when talking about killer hair extensions.

Suicide Club’s brutal opening subway sequence is immediately followed by yet another incident of puzzling self-destruction. On the top floor of a dark hospital after hours, two night nurses are laughing and giggling, humming along to a song called “Mail Me” by a young J-pop group named Dessert. One leaves to buy some food, and when she returns, the other jumps out the window. The first nurse soon follows suit.

This immediately alarms the authorities, and the detective Kuroda and his team begin to suspect that this will not be an isolated incident. They receive a strange call from a young girl who identifies herself only as The Bat, and she informs them of a bare-bones website with nothing but red and white dots. Hours before the Ueno Station incident, 54 new dots appeared on the site, one for each girl that jumped, implying that these suicides were deliberately planned. Kuroda decides to keep this information on the down-low, to avoid wide-spread panic.

The very next day, a group of high school students gather on the roof of their school during a lunch break. One student begins joking about forming their very own suicide club, and another student dares him to jump off the building. He takes this seriously, and stands at the end of the ledge. As he does so, an entire group of students joins him, and all but two jump to their deaths. The observing students begin screaming, trying to coax the final two away from the ledge. The boy who chickened out is so startled that he loses his balance and falls. The final girl turns around to the other students and, in a very serious tone proclaims, “We’re the Suicide Club’s founding chapter” as she jumps as well.

At the site of each suicide, the police discover a white handbag that reeks of death. Inside is a large roll of human flesh, each piece tied to the next. It becomes evident that every piece of skin belongs to different person. A young girl named Mitsuko walks casually along the street, as her boyfriend falls from atop a building and lands on her. She in unharmed, but he perishes quickly. Mitsuko is taken in for questioning, but she insists she knows nothing. She is strip-searched, and one detective notes a butterfly tattoo on her shoulder.

Kuroda receives another phone call from what sounds like a young male child. He claims that, “There is no Suicide Club.” After each sentence, the boy coughs inexplicably. He informs Kuroda that in a few hours, there will be another group suicide at the same location that the first occurred. Kuroda and his task force investigate Ueno station, but there are no suicides. This leaves the detectives discouraged and baffled.

There is one aspect of Sion Sono films that I’ve deliberately withheld until this point – they tend to be dramatically uneven, in a very intentional way. The setup so far is moderately intriguing, but the second half of the film takes a controversial (and in my opinion very necessary) turn down the dark rabbit hole of the nature of suicidal ideation and generational divide. I don’t wish to fully spoil the experience of the film’s final act for anyone, but I’m going to anyway. I haven’t really revealed many surprises at this point, so it you’re intrigued, I’m giving you one final spoiler warning.

After the non-incident at Ueno, another batch of suicides takes place, but in disparate locations. The Bat watches as several more dots appear on the suicide club website, and there’s a thematically-important montage of death set to a happy song in which a gentle male singer engages in “call-and-response” style vocals alongside a choir of children. This montage covers five instances of suicide as several young women on the streets of Tokyo hold up signs that say, “Jump here.”

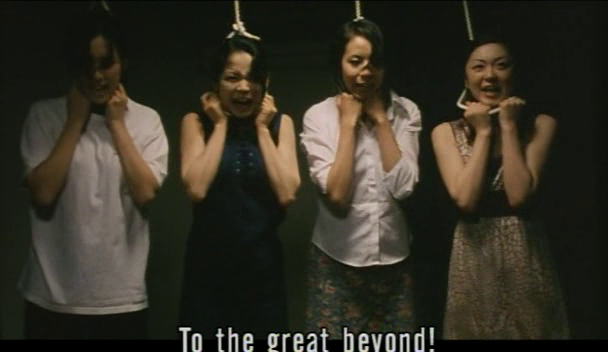

1) Four women are shown having a very “theatrical” discussion over a plain background. The dialog occurs as voice-over at first:

“Don’t leave to tomorrow what you can do today.”

“Japan’s too complacent.”

“I used to shoplift.”

“We’re sinners.”

“Yes, life is a sin! You just cause trouble for others.”

“Kill yourself before you murder someone.”

“That’s the spirit! Dismissed”

“Ropes. Ladies!”

“To the great beyond!”

All four women gleefully hang themselves.

2) A pair of stand-up comedians await their turn at a variety show. Once on-stage, they preface their comedy routine with, “Have you noticed how quickly fads come and go these days? Take cell phones…” We miss most of the show, but their grand finale begins with, “You hallucinate,” clearly the punch line to a joke. Immediately, the other comedian says, “Go kill yourself” as the audience continues to laugh. They stop laughing as the other performer stabs himself in the neck with a switchblade. His partner calmly ends his act with, “Thank you very much.”

3) A middle-aged man listens to the comedy routine on the radio with a contemplative look on his face while he waits for customers at his food stand. He removes his wedding band and takes an entire bottle of pills.

4) A young, depressed girl sits in a corner in her kitchen next to an oven, nostalgically gazing into a small box. Her expression changes suddenly, and she dives head-first into the oven, Plath style.

5) A family watches the J-pop band Dessert on television as they advertise a brand of chocolate bars. A very young girl approaches her mother in the kitchen, who is preparing dinner by slicing what appears to be a tube of dough. The girl begs her mother for chocolate, and is met with, “If you’re a good girl!” The mother begins cutting into parts of her fingers (and eventually severs her own hand) as she smiles. Too young to fully understand, her daughter runs out of the kitchen and tells her father, “Mom’s funny.” The family continues to watch television.

This sequence ends with a brief statement from one member of Dessert:

“Everyone’s acting funny these days, we hope this song will cheer everybody up!”

Each one of these sequences presents a different perspective on suicidal motivation. The odd group of women seem to argue that humans are evil by nature, and that by ending your life, you’re sparing everyone the harm and anguish you would otherwise cause to the world. This act is portrayed by its participants as the only morally-rational conclusion to the conundrum of the dark nature of humanity, and like the rest of the film, its extraordinarily silly presentation is meant to highlight just how twisted and absurd this train of thought really is, regardless of how rational it seems in the moment.

The second incident introduces suicide as a pop culture fad, comparable to the perception of cell phones at the time, which were just beginning to become common during this era. After humorously berating the nature of fads in their performance, the comedians’ ultimate punch-line is to engage in the very act they previously condemned. Dismissiveness and disapproval of generational fads is a common occurrence in most if not all modern societies, and fads are often, by default, absurd. However, the criticisms lobbed at these fads by older generations are often equally as absurd (and potentially harmful.) This incident exists in part to criticize adults who didactically pose the question, “If it was cool to kill yourself, would you do it?” in response to their own disapproval of things they cannot understand because of a generational divide.

The third incident shows us suicide as a result of ennui and lack of economic mobility. The food stand owner shows no emotion during this entire sequence. He has no customers, and he’s sitting in front of piping hot food that he recently prepared, just like every other day. We can infer by the removal of his wedding band that he is likely trapped in a loveless marriage. When he decides that he’s fed up with his mundane existence, death seems to be the ultimate solution. Because of his life situation and position within Japanese society, it is very likely that his economic mobility will be limited for the rest of his days. Recognizing the futility and meaninglessness of his existence, he succumbs to a sort of cultural nihilism, requiring only the subtlest prompt (someone saying “kill yourself” on the radio) to go through with ending his own life.

The fourth incident is unique in that it does not involve an adult like the other four. We can infer from the way the young girl interacts with the ornate box she holds that it likely belonged to a former lover. This partner was an important part of who this girl was as a person, and once she lost that connection with him or her, she also lost her own sense of identity. She views suicide as a way to repair that connection to herself – a defiant act to both end the pain and exercise the agency she now possesses as a single woman. In her emotional state, this is the only way she feels she can achieve this, however wrong-headed her perspective is.

The fifth incident is representative of familial disconnection. The woman preparing food in the kitchen is completely separate from the rest of her family, who are watching television in another room, oblivious to her suicidal actions. They seem like a fairly traditional family, and perhaps Sono uses this as a condemnation of the loneliness one can feel when the whole of your identity is tied to a family unit. Even the small separation of being in an adjacent room leads this woman to kill herself, because without her family unit beside her, she has no self-identity and therefore no reason to live.

That’s an abnormal amount of thematic territory covered in a montage that lasts under two minutes, and there are other sequences like it in the film. They go by so fast that it’s easy to interpret this as bombardment, and that’s precisely the intention.

Another point of note in the fifth incident is found in the young girl’s contribution. She is enamored with the pop band Dessert, and their endorsement of chocolate is enough for her to beg for it. This mirrors the primary interpretation of the film’s plot – that Dessert acts as a “Pied Piper,” leading many who are exposed to their music to commit suicide. This is still the prevailing theory among most audiences, but like any concrete assessment of Suicide Club’s plot, it doesn’t explain everything. For example, the two nurses at the beginning of the film do make their decision to jump off the building after listening to Dessert’s song, “Mail Me.” However, the man who runs a food stand is not listening to Dessert, nor are the aforementioned comedians. There are many more counterexamples, although most of those can be debunked by thinking of Dessert’s influence as less direct, something that seeps into your subconscious, rather than eliciting an immediate suicidal reaction. The Pied Piper theory is also mirrored in the call-and-response nature of the song played over this montage – a man sings, and a whole chorus of children repeat his words.

The fifth incident’s commentary on familial disconnection is mirrored in the very next scene. Kuroda arrives at home, exhausted. As he removes his shoes while sitting on the ground, his daughter approaches behind him, covered in blood. After she greets him with, “Welcome home dad,” Kuroda simply says he’s exhausted, and she lowers her head while walking away. While he doesn’t see her, he does notice the trail of blood she has left behind while walking away. “Track 8: Jump Here” is written in large font on a wall. His entire family is now dead, and they all have pieces of skin missing, like the skin fragments found at each of the “crime scenes,” proving that they were the victims of the very same phenomenon that Kuroda has been investigating. He has been so wrapped up in solving the mystery of Suicide Club that he failed to notice what was happening to his own family.

The detectives all gather at Kuroda’s home. One detective says, “This isn’t suicide, it’s murder.” Another detective, Shibusawa, retorts with, “Tell me…which is murder, and which isn’t? Is it murder starting today, or is this a special exception? It was murder from the start!” This indictment is particularly important thematically. At first, this seems to be directing the blame at Dessert, if you’re sticking to the Pied Piper theory. However, when you look at the breadth of systemic issues that Suicide Club highlights, I don’t think it’s that simplistic. This is Sono pointing his finger at Japanese culture, and saying, “You did this!” Dessert is just a stand-in for the shiny veneer placed over a toxic cultural perspective.

Kuroda receives a call at his apartment from the mysterious boy with the chronic cough. Once Kuroda is on the line, another boy begins speaking with him. Kuroda begs the boy to explain why he did it, and the boy denies culpability. Several children’s voices begin delivering a speech:

“Do you understand? I understand our connection. I understand your connection to your wife. I understand your connection to your children. But as for your connection to yourself…If you die, will you lose the connection with yourself? Even if you die, your connection with your wife will remain. So will your connection with your children. But if you die, will you lose your connection with yourself? Will you live on? Are you connected to yourself?”

Another child’s voice continues, this time berating Kuroda.

“Why couldn’t you feel the pain of others as you would your own? Why couldn’t you bear the pain of others as you would your own? You are the criminal. You could only think of yourself. You’re scum. Scum!”

Kuroda grabs a gun and points it at a mirror before turning it on himself and declaring, “It’s no use. They are not the enemy” and pulling the trigger.

This speech, and one later in the film, continue to reinforce the film’s themes in a very cryptic way. It’s important to note that this scene involves an adult talking to children, and the adult proclaims that these children are not the enemy after they indict him as the real criminal. This represents a reconciliation of sorts for the generational gap the film points out quite frequently, but often becomes lost in more simplistic interpretations of the film, particularly the perspective that its only theme is, “suicide bad.” The obscure and perplexing nature of this speech (and the film itself) sometimes appears to be a stand-in for the way youth appear to adults. After all, the cultural issues that influence suicide come from a society shaped by these adults. Kuroda seems to realize that ‘he’ is a part of the problem, which means he is partially culpable for his own family’s suicide. By his own culture’s norms, taking his own life is the only moral action he has left; his only redemption.

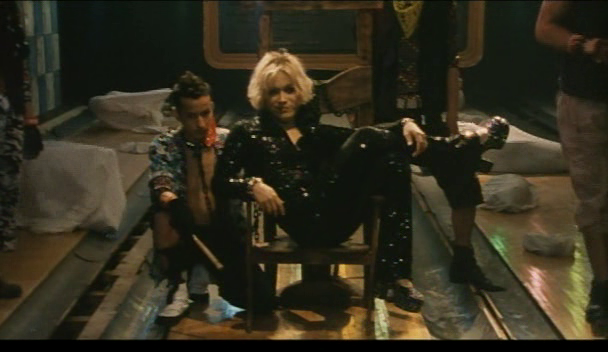

While the previous events have unfolded, the young hacker known as “The Bat” has been watching with her friend from afar, searching the internet for clues. The Bat is revealed to be a young girl named Kiyoko, and she is captured by a group of young hooligans led by wannabe glam rock icon Genesis. She is taken to Genesis’ lair, an abandoned underground bowling alley, which is the stuff of nightmares. Throughout the lair are what appear to be both humans and animals stuffed into fully-closed sacks, squirming for freedom. The thugs brutally torture (and eventually rape) these mostly-unseen victims before Kiyoko’s eyes as Genesis conveys his master plan, using her to tell the world that he is the leader of Suicide Club. In one of the most disturbing and eccentric scenes of the film, he performs a song with his band of thugs.

Genesis’ sequence is probably the second-most remembered part of this film. His character is played by Rolly Teranishi, the lead singer of a popular glam rock band called Scanch, and his appearance is very Bowie-inspired. He was quite well-known in Japan at this time, so it’s an interesting casting choice. His song, which includes the chorus, “Because dead shine all night long,” is at first a romanticization of death. Genesis expresses that he wants to die as beautifully as Joan of Arc inside a Bresson film, a reference to the silent 1928 classic The Passion of Joan of Arc. The song ends with a verse about a young boy dying tragically (but beautifully, according to Genesis.)

“A guileless boy but five years old

stares blankly in the face of death

while his heart

is cut and torn away.”

When Genesis is apprehended, he proudly proclaims that he is the leader of Suicide Club to the press, and now that the media has someone to blame, the case is closed in the public eye. He represents the dark side of youth culture – the romantically nihilistic fetishization of fame at any cost. He openly admits to committing a crime he did not and could not have committed, simply for the attention it will bring him. At the same time, he is as guilty as Kuroda, for very similar reasons. This is, in my opinion, Sono’s way of shifting the blame for Japanese suicide culture to both the young AND the old, and that focusing squarely on which generation is to blame is missing the point entirely. One generation set the stage for this, but the other perpetuates it.

Genesis’ arrest leads directly into a music video for Dessert’s song “Jigsaw Puzzle.”

“The world is a jigsaw puzzle.

Somewhere there’s a fit for you.

A place where your

puzzle piece belongs.

Don’t fit you say?

Then make it so.

There’s nowhere

for my piece to go.

Find a match

that lasts forever.

Perhaps I better say so long.”

Of Dessert’s songs, this one is the most straight-forward. The world is complicated, but you just have to find your place in it. If your jigsaw puzzle doesn’t fit, however, then you must make it fit, permanently. Therefore, you should “say so long.” Goodbyes tend to be code for suicide throughout the film.

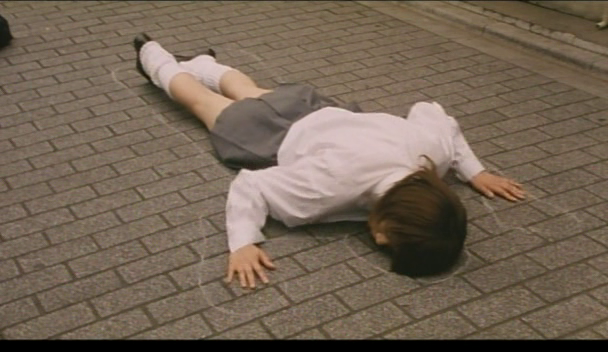

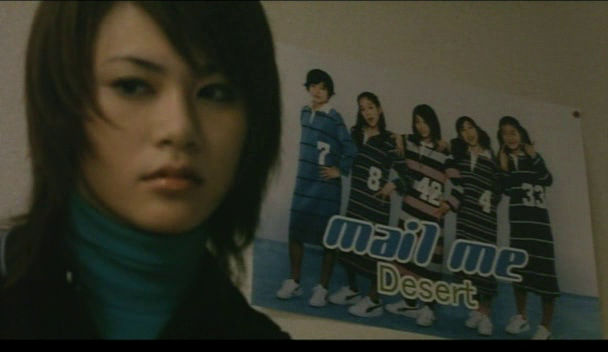

At this point, the film still has over 20 minutes left, and the main character, Kuroda, is dead. Our lead shifts to Mitsuko, whose boyfriend fell to his death and landed on her earlier in the film. She finds the chalk outline of her boyfriend’s body, and lies down to fit its form as she solemnly mourns his loss. Mitsuko goes to her boyfriend’s house, and searches his room for any answers she could possibly find as to why he might have killed himself. She finds the following poster, with markings on it.

Each number on the girls’ shirts corresponds to a digit on a phone keypad, and the number of fingers they’re holding up next to that number represents how many times that button must be pressed. This is back when the “abc” texting method was still the predominant text entry method for cell phones. For example, the number 3 represents the letters D, E, and F. If you press 3 once, you get a D. Press it twice, you get an E. You get the idea. When Mitsuko enters the code into her phone, it spells out, “Suicide.” Even with the fact that Mitsuko’s boyfriend had circled parts of this poster, it’s still a pretty egregious plot convenience, and I do recognize that as one of the film’s greatest flaws.

As soon as she cracks the code, she receives a call from the same boy who spoke with Kuroda. “There is no Suicide Club, but come on over.” Mitsuko then receives a message on her boyfriend’s computer that tells of an upcoming Dessert concert, and she runs to the venue. She sneaks in through the back and finds a group of young children playing, some of them in yellow raincoats. After following a young girl behind the curtain of the auditorium’s stage, the lights go out and the curtain rises, revealing an audience full of clapping children, with Mitsuko on stage. They begin asking her questions.

“Why did you come? Did you come to repair your connection with yourself? Or did you come to sever that connection? Are you connected to yourself?” Mitsuko then proudly proclaims, “I am me, and I’m connected to myself!” The children clap gleefully, and one boy continues to speak.

“Are you related to you? Like between you and me, victim and assailant…you and your boyfriend. Can you relate to yourself? Are you related to yourself? Are you sought by yourself? When rain dries, clouds form. When clouds moisten, rain forms.” The curtain falls.

This final speech is full of the same cryptic dialog as before, but the tone and content are different. When the children speak to Kuroda, they are disapproving because of his disconnection with his family and himself, and the consequences of his disconnection. On the other hand, Mitsuko is celebrated by the children. She is a victim in this, but when her boyfriend died, she did not lose her sense of self, as it is implied that the girl from the earlier montage had (the one who died Plath-style.) She is connected to herself, and is ready to live on.

“When rain dries, clouds form. When clouds moisten, rain forms.” This statement at first seems unrelated to what the children are talking about, and comes across as unnecessarily cryptic (in an already oblique speech.) However, it is very clearly a comment on the cyclical nature of *something.*

When the speech is over, Mitsuko is led to a dimly-lit hallway. The children with yellow raincoats stand by a row of women who are on the floor, facing the wall. A gimp-esque figure hands the leader of the children a machine, and one by one, he uses it on each of the women to remove a piece of skin from their backs, including Mitsuko. The children stand in a circle with a roll of flesh in the center.

The detective Shibusawa finds the roll of flesh at the scene of another suicide. He quickly unravels it, and finds Mitsuko’s butterfly tattoo. Alarmed, he tracks her down to the train station. A chorus of cell phones begin ringing at the same time, and all of them are the melody to Dessert’s song “Mail Me.” Many girls dressed in school uniforms, including Mitsuko, line up by the train tracks. Shibusawa grabs Mitsuko, fearing that these girls are about to repeat the incident at the beginning of the film. She resists, the train arrives, and she stands in the doorway after boarding, giving Shibusawa a confused look.

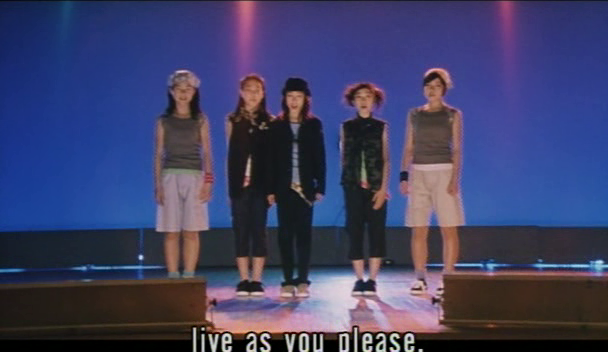

Dessert performs, and announce that it will be their final performance. Before the song begins, they declare that their final message to their fans is, “Live as you please.” The lyrics to the final song are a bit different than previous ones.

“Light yourself with life.

Light yourself with love.

Light yourself with memories.

All it takes is just a little

heart and courage on your part.

Turn yourself around and

take it once again from the start.

Though you may feel out

of touch at times

or fear a wicked spell

has got your life in hand.

Scary, it’s true.

But we’ll be happy too.

Now do you really

want to say good bye…

…and leave me high and dry.

As we go, we’ll forget the pain.

We’ll find life again.”

It would be very easy to interpret this as yet another glorification of suicide, but I really don’t believe this to be the case at all. In fact, quite the opposite. There is a line about fearing that a spell has ahold of you, which could support the Pied Piper theory, but consider that this song occurs immediately after Mitsuko has faced the children, declared her connection to herself, become inducted into Suicide Club, and decided not to end her own life. I see Mitsuko’s story as an arc. She felt the despair of losing her boyfriend, but she did not succumb to suicide. She did not jump at track 8 as the other girls did.

With that in mind, the song seems to be talking about how difficult living can be, but if you’re able to fight through the pain, it can be wonderful. It is an acknowledgment that life can be more scary than death sometimes, but also that death is not the solution. “Scary, it’s true. But we’ll be happy too. Now do you really want to say goodbye and leave me high and dry.”

As previously stated, saying goodbye has been associated with suicide throughout this entire film. However, this song questions whether you really want to say goodbye or not. I see this as Dessert encouraging their audience to press forward and live their lives, and I believe it to be the biggest argument against the Pied Piper theory. There are elements of that at play, but it’s almost as if Dessert themselves have gone through an arc throughout the film, now actively discouraging the behavior they may have encouraged prior. Perhaps it was simply pop culture that the second half vilifies as the real culprit, and now that Dessert has performed one last time, they will no longer be trendy – and neither will suicide.

Still, there’s no denying that the ending is ambiguous, and there are plenty of unanswered questions. Even after Mitsuko declared her connection to herself, she still went through with the skin ritual, the creepy children still exist, and while Mitsuko didn’t jump in front of a train, who’s to say she isn’t on her way to hop off a building? There’s a reason for this ambiguous ending:

Suicide Club was always meant to be a trilogy.

While the final film in this proposed trilogy has never seen the light of day, there is in fact a second film. Noriko’s Dinner Table (2006) is both a prequel and sequel to Suicide Club, and it’s almost as great as the first film, though very different. It focuses much more on the generation gap themes, and sheds some light on the nature of Suicide Club as an organization (sort of). It’s a film that does tend to raise as many questions as answers, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t worth a watch.

There are also two other works in this universe. Suicide Circle: Complete Edition is a novel written by Sono, and it supposedly it ties Suicide Club and Noriko’s Dinner Table together even further. I wouldn’t know though, because there is no English translation that I’m aware of. There definitely isn’t an official English release. There’s also a manga simply titled Suicide Circle (which is really a better translation of this film’s title than Suicide “Club”), and while it begins with the same incident, its story veers off drastically from that point, instead focusing on a lone survivor of the 54 girls who jumped in front of a train.

We’ll likely never have an objective interpretation of what’s really going on in Suicide Club, and I’m completely okay with that. It could be viewed as incomplete, but even if that’s so, it’s still dense with social commentary and plot points that lend themselves well to theorizing. It’s also still an important film in regards to understanding Japanese suicide culture, and an immensely dark and transgressive work of fiction. There’s nothing quite like it, and it pains me to hear negative criticism about how shallow it is thematically. When you dig a little deeper, there’s more territory covered under the surface than most films could hope to tackle in a series of ten installments.

Suicide Club is, in my opinion, the most unfairly underrated film of the past 20 years. I am connected to it. It is connected to me.

And I have no desire to sever that connection.