Before I dive right into this, I really have to stress that Life Itself inspired a level of hate and frustration in me that’s difficult to express in words. This will not be kind, and it will definitely include strong language, broad generalizations, and hateful insults lobbed at actual human beings with feelings. Sorry.

In 2016, NBC began airing a show called “This Is Us.” It took some time to gain traction, but by the end of the first season, it was one of the most talked-about shows on network television. It quickly gained a reputation for being excessively manipulative in its approach to sensitive subject matter, as the show essentially prompts the audience to cry the way sitcom audiences are prompted to laugh. I only made it through the first season, and while it was more well-written than I expected, it was hard to shake the implications of that criticism. It did earn some of its “cry now” moments, but they’re so densely ingrained in every episode that it loses impact quickly.

This Is Us drew significant inspiration from a sub-genre I loathe even more with every new entry: hyperlink cinema. These films simultaneously follow several characters who are all linked together in some way, whether literally or thematically. To me, Magnolia is the king of the genre, Short Cuts is its jealous uncle, and D. W. Griffith’s Intolerance is the disgruntled great-grandfather you could never bring your non-white girlfriend home to.

The nature of the link between the interwoven story-lines generally makes or breaks these films. In Robert Altman’s Nashville, the link is simply the city of Nashville, and character arcs don’t necessarily intersect very often. In God’s Not Dead, the link is a nasty car accident and a Newsboys concert. In This Is Us, our link is a set of triplets and their relatives. The show occurs over multiple timelines as well, and it uses this structure to deliver its plot twists. Because it’s a show, there isn’t really a single “convergence point” as there is in a hyperlink entry like Magnolia, but it’s worth noting that this is a signature of the genre.

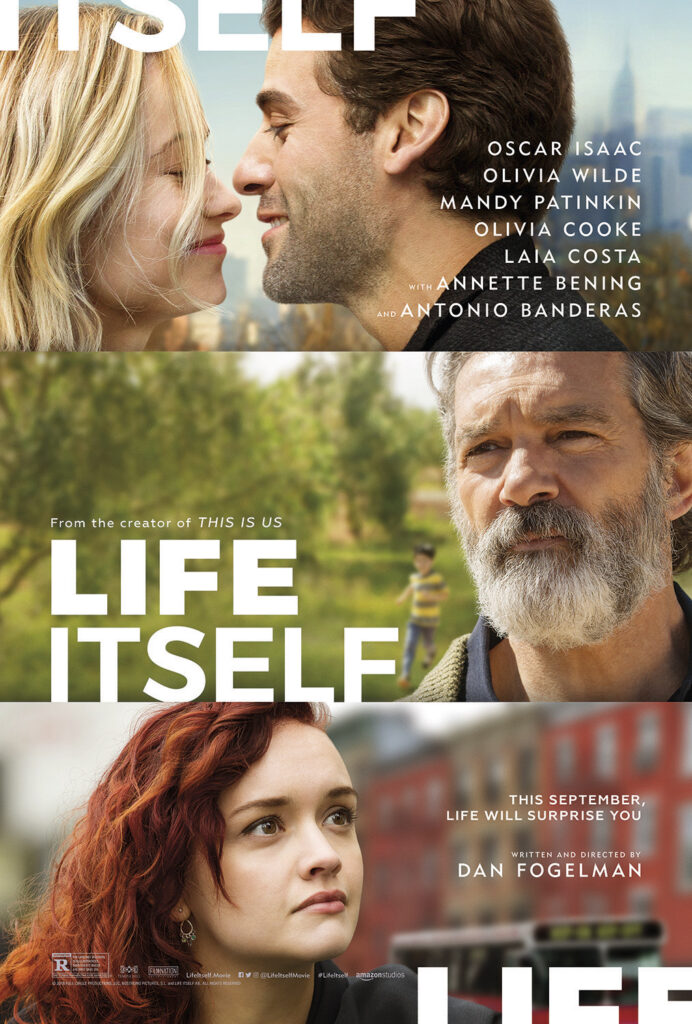

This Is Us is not series creator Dan Fogelman’s first hyperlink rodeo. He penned 2011’s Crazy, Stupid, Love, which followed a similar formula, although to a simpler degree. After the success of This Is Us, either Fogelman or the people generously tucking dollar bills into his G-string decided to capitalize on the success of the show by hiring talented actors and rushing out a shitty script. This became our subject: Life Itself.

This film is what happens when you hire a pretentious writer and force him to direct his own work in spite of the fact that he has only one other directing credit, and then try to condense an entire season of This Is Us into a single two-hour experience. It is absolutely as messy and weird as it sounds.

I guess I should throw out a spoiler warning for this one, because there are definitely some surprises in the film. They aren’t the good kind of surprising, but there are “unexpected” moments at just about every turn. Quite frankly, I want to ruin this movie for everyone, because any disincentive to see it is practically a public service. Before you check it out on the basis that you “may” like this film, know that it absolutely deserves its 11% score on Rotten Tomatoes. You have been warned.

Chapter One – The Hero

This is not an analysis of the hero of Life Itself. In my opinion, it’s difficult to call anyone in this film a hero, because nearly every character is obnoxious or one-dimensional. ‘Chapter One – The Hero’ is the title of the first section of the film, and it’s one of five.

From Life Itself’s opening monologue, it becomes all too apparent that, narratively, things are going to be a bit rocky. In voice-over, Samuel L. Jackson tries and fails to introduce several characters. The first is an inconsequentially-gay character talking to his therapist. Just like our audience, Jackson grows tired of his own shitty descriptions of this character, and moves on to describe the therapist Cait, played by Annette Bening in one of the worst examples of under-utilization this year. Once again losing his focus, Jackson introduces Will (Oscar Isaac), who acknowledges that he’s a “fan of [Cait’s] work” at the least opportune moment. Like an idiot, Cait looks back while standing in the street, and is hit by a bus.

Perhaps this is Annette Bening’s desperate cry to be removed from this shitty movie.

But wait!

This is all a screenplay that Will is working on called, “Samuel L. Jackson, Unreliable Narrator.” Get ready for more unnecessarily meta plot revelations, because this movie thinks it’s clever as fuck. The inconsequentially-gay man was a character in the script, but in “real life,” he is replaced by Will, who is still talking to his therapist Cait, still played by Annette Bening. Sorry Ms. Bening.

Will is sad because his wife Abby (Olivia Wilde) has left him. Immediately after this event, Will was institutionalized, and it’s pretty apparent that his visit with Cait is court-ordered. He goes on to explain way more about Abby’s life than we needed to know. In flashback, Abby drones on and on about Bob Dylan while in bed with Will. He’s rather uninterested, and while it’s clear the film wants us to believe that Abby’s points about why Dylan’s work in the 90s was so great is some kind of a touching revelation, it’s far easier to sympathize with her husband, who wants nothing more than to shut her up and make love. This lecture is supposed to be thematically tied to the narrative somehow, and it will be referenced far, far too often.

But wait!

Abby gets out of bed, and we get another plot revelation: she’s super pregnant!

As the Abby flashback continues, we find out that her parents died in a horrible car crash when she was seven, and she was briefly the star of her own rape/revenge thriller, threatening to murder her molesting uncle. In college she meets Will, and the two are married in a little over a year’s time. Will’s mother is overjoyed to have a daughter-in-law with dead parents, and says so outright. Will apologizes for his mother’s tasteless comment, but Abby rolls with it and takes the mother’s side, pointing out that there are certain advantages to a child having one set of grandparents.

One day, Abby busts into their home as Will is hanging out with friends, and while in the midst of a manic episode declares that her thesis will be on the idea that “life is the ultimate unreliable narrator” because it surprises you at every turn. Yes, that thesis is precisely as flimsy and reductive as it sounds, and yes, it will be returned to in nearly every narrated portion of the film. This entire film is narrated. And no, it will never fully make sense.

But wait!

Will is completely delusional. His therapist begins to pry out the real story. After Abby proclaims that she wants to name their child Bob Dylan if it’s a boy, Will stops along the sidewalk, an appropriate reaction to such an outrageously idiotic statement. She walks to the middle of the road like a jackass, turns around, and begins to have a full-on conversation with Will. Again, like a jackass. Mercifully, there’s a giant bus headed her way that will shut her up for good, just like Will’s therapist in his awful Samuel L. Jackson script. Unfortunately, this won’t be the last we see of her, because this is one of those films where characters talk to each other out loud about the events we just witnessed and their significance, and even dead characters are allowed to provide meta-commentary. Characters walk around freely as they explore flashback sequences, and make thoughtless remarks about their former selves.

Will is reminded by Cait that while Abby died instantly, her child survived. He can’t take it anymore, and he blows his brains out in Cait’s office.

The bus accident is the point where all of the different story-lines will converge. We will be reminded of this every time relevant information enters the picture.

Based on the way I’m describing this so far, it should be pretty apparent that I have problems with pretty much everything that happens in this first act. What isn’t so clear is that some of this is supposed to be funny. Let’s break it down by the film’s stance on a few key points in this section of the story:

Samuel L. Jackson poking fun at a gay man seeking therapy:

Funny!

Cait being hit by a bus:

Not funny

Cait being hit by a bus once the audience knows it’s part of a script:

Funny!

Will seeing a therapist:

Funny!

Will seeing a therapist because his wife is dead:

Not funny

Abby boring Will (and the audience) with Bob Dylan worship:

Not funny

Abby’s manic episode in which she relays the central theme:

Not funny

Will’s mother declaring that she’s happy that Abby’s parents are dead:

Funny!

Abby’s parents dying in a car crash:

Not funny

Abby being molested by her uncle, but eventually standing up to him:

Funny!

Abby being hit by a bus:

The jury is still out on this one, because it’s some combination of both.

This entire first chapter is an exercise in tonal whiplash. This could have been a very dark comedy, an interesting experimental film, or a straight-up drama. Instead, it opted for all three, and as a result it feels like an all-out assault of absurdity. This is shitty art imitating life imitating shitty art. Every frame begs you to take its profundity seriously, and the result is confusing and pathetic. Even worse: we’re not even close to the halfway point.

Chapter Two – Dylan Dempsey

After Will’s suicide, his creepy parents take custody of his daughter. Dylan Dempsey is played in part by another Olivia that sounded like a good casting choice at the time, Olivia Cooke. Dylan’s grandmother dies when she’s six years old, and Dylan’s dog dies when she’s seven. It sounds like there’s a parallel being created here, but there isn’t. These events just serve to show the audience that, from birth, Dylan’s life has been influenced by death. Her grandfather has a talk with her about how there will be “no more dying” in this family. We see two sides of this conversation: what the characters say, and what they actually mean. This scene is so close to being heartfelt, but the movie hasn’t earned the right to give me feelings. It’s also just a cheap rip-off of several scenes in Annie Hall.

21-year-old Dylan is cruel to her grandfather, because any 21-year-old would be, and she is now the lead singer of a punk band called PB&J. She gets on stage and starts singing a pretty typical and boring solo cover of Make You Feel My Love by Bob Dylan. After a verse, a chorus, and a sincere plea from the audience to please make it stop, this turns into a punk cover of the song. Olivia Cooke’s performance of the latter part of the song is the most lazy and painful cover I’ve heard in years, and it’s clear that it isn’t supposed to be.

After the show, Dylan is backstage selling merch, which apparently includes actual peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. As she makes out with her female friend, some girl begins filming them. Dylan lashes out, breaking the girl’s phone and smearing a pb&j sandwich all over her face. It’s a hilariously perplexing moment, and while it’s supposed to be there to indicate that Dylan is troubled, I feel like that’s a picture we got perfectly fine BEFORE she picked up that sandwich.

But wait!

Dylan smokes a joint on a park bench, has a flashback to her mother’s death, and is then asked by Rodrigo if she’s alright. Who is Rodrigo? It’s better if you don’t ask, because then we’d have to move on to…

Chapter Three – The Gonzalez Family

Transitioning to Spain, Antonio Banderas plays Vincent, the boss of simple field hand Javier Gonzalez. Vincent tells Javier about how he enacted revenge on his abhorrent father by…waiting for him to die, inheriting money, and being wealthy. For whatever reason, Vincent offers to set Javier up with some land.

Javier and his wife Isabel sire a child and name it Rodrigo. Because they’re a Spanish family with limited means, they are “happy poor people.” Vincent hangs around the house while Javier is away, very much appearing to have designs on Javier’s wife and child. Given how mean-spirited the film has been up to this point, I assumed Vincent was going to rape Isabel and kidnap Rodrigo, because that would be the logical conclusion. Instead, Javier becomes jealous that he can’t provide the wealth that Vincent could, and banishes Vincent from their home in an unnecessary show of machismo.

After Vincent plants the idea of going to America in Rodrigo’s head, the child becomes obsessed with taking a trip to New York City. To demonstrate to his family that he’s not a complete loser, Javier takes his family to NYC, where they act like irresponsible tourists. The family is riding in the back of the bus, and Rodrigo slowly makes his way to the front, talking whimsically with each stranger he passes by, all of whom are very friendly, because that’s clearly what riding on a bus through so-so parts of NYC is like. When Rodrigo reaches the front of the bus, the driver is distracted by his overwhelming cuteness until running into some pregnant woman named Abby. Rodrigo looks on in confusion, and we finally figure out why this entire chapter even exists.

But wait!

After the trip, Rodrigo suffers from kiddie-PTSD, and his parents don’t know how to handle that shit. Javier allows Vincent to return to their home, which helps Rodrigo significantly. Hopefully realizing that he’s a hard-headed anti-intellectual coward, Javier abandons his family completely after suspecting that they love Vincent more. For whatever reason, Isabel still holds on to her love for Javier.

Chapter Four – Rodrigo Gonzalez

Rodrigo grows up and goes to school in NYC, of all places. All that trauma must have been just a little overblown. His mother Isabel is perpetually dying of cancer back home in Spain. He meets a controlling, vapid girl named Shari, and they begin dating. The narrator at this point indicates that, “This will be one of the most important days of Rodrigo’s life.”

Shari tells Rodrigo that she’s pregnant, and leads him on with this lie for an entire morning. Eventually, she reveals that it was an April Fool’s joke, a custom that Rodrigo was not aware of due to being culturally ignorant. Nonetheless, it was a shitty April Fool’s joke, and Rodrigo breaks up with her.

But wait!

That’s not the reason this is one of the most important days of Rodrigo’s life! Upon arriving home, he receives a phone call that his mother is dead. Javier had returned briefly to say goodbye, and had apparently been in the loop as to how the family was doing through letters written by Vincent. Isabel spends her final moments with Javier, something he clearly didn’t deserve.

Distraught, Rodrigo decides to go for a run to let off some steam. That’s when he runs into Dylan, sitting on a park bench right near the location where her mother was mowed over by a bus.

But wait!

Chapter Five – Elena Dempsey-Gonzalez

At some point, the narrator shifted from Samuel L. Jackson to this boring mess, Elena Dempsey-Gonzalez. Elena wrote a book called Life Itself that chronicles the history of how she got to be where she is today, and the film we’re watching is apparently an adaptation of this book. For as long as she’s been our narrator, she’s been standing in front of an audience on her book tour, reading passages aloud with the same energy and conviction reserved for the book report of a sixth-grader who hasn’t read the book. The film begins to montage like fucking crazy, and we get a forced “touching moment” speech that almost reiterates Abby’s shitty thesis, but not quite. That would require focus.

Life Itself is not the beautiful mess it aspires to be. It’s not the touching drama its muted advertising and annoying IMDB banners would have you believe. It’s an awful retread of patterns formed in This Is Us, with no understanding about what made that show appealing. It’s also a blatantly cynical way to capitalize on the success of the show financially, and thanks to film critics and poor word-of-mouth, that attempt was a tremendous failure. The following factoid is the only thing about Life Itself that filled me with as much happiness as the Annette Bening bus scene:

It had the second lowest opening box office returns for a film with a wide release since 1982.

When some asshole makes a cynical cash-grab film, it’s sad when it achieves some level of success. That success is often what triggers this accusation in the first place. In that regard, this film’s failure is almost inspiring…

Except that you know it’s going to blow up on Amazon. God dammit.

I give it two joyful Annette Bening traffic accidents out of ten.