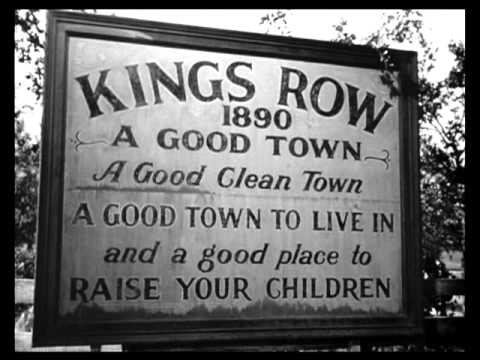

Kings Row is the punch-line to the complicated setup, “What do Ronald Reagan, the opening theme of Star Wars, implied incest, and the advent of psychoanalysis have in common?”

As a sucker for old Hollywood melodramas, I’m not unfamiliar with Ronald Reagan’s film career. There are some very distinct differences between Reagan the actor and Reagan the politician. Just to get this out of the way, I’m a fan of neither.

When we talk about Reagan’s film career in 2018, we do so rather flippantly. His stint in Hollywood is practically trivia, and while his name usually appeared in the third position (or below) on any casting list, he did make an impact on the industry. Because of his political career, it’s pretty easy to forget the man had 69 credits to his name before retiring from film altogether in the late ‘60s. In spite of that solid work ethic, Reagan never really churned out a career-defining performance, with one very, very notable exception. I really can’t say his acting in Kings Row is anything beyond “good,” however, this was the movie he referred to most often. The greatest aspects of the film have absolutely nothing to do with Ronald Reagan.

Reagan wanted to make absolutely sure that, even if the American public were to ignore the rest of his filmography, everyone knew about Kings Row. “Where’s the Rest of Me?”, the most quoted line of the film, was the title of his biography. Stories about his method acting during the filming of that scene were thrown around quite often, as he would point out that it was shot under some degree of duress, and in a single take, with plenty of input from real amputees.

The film’s score is notorious for two reasons. John Williams openly admits to taking inspiration from the score when composing for the original Star Wars, almost four years before Reagan’s presidency. Also, the white house requested the main theme of Kings Row be played at his inauguration, a delightfully tacky and self-aggrandizing move that’s a whole lot easier to laugh at in 2018. When you take certain aspects of Reagan’s presidency into account, his role in this film couldn’t be more ironic.

The real irony is that Kings Row was a film that spat in the face of the Hays Code, a strict series of moral guidelines that determined whether or not a film was suitable for public consumption. The enforcement of this “objective moral compass for the masses” was the source of many troubled production histories throughout its reign from the 1930s to the late 1950s.

The novel Kings Row was based on is far less dodgy when it comes to its portrayal of murder/suicide, mental illness, incest, homosexuality, euthanasia, nymphomania, gender equality, adultery, class warfare, sexual repression, and sadism than its film adaptation. The point is, it was a battle to get this film made in the first place, and the final product was significantly neutered. It took years of script re-writes to get the film to a point where censors would even approve its creation, and the very idea of adapting such a novel was against what the Production Code Authority had in mind at the time.

The establishment of the MPAA’s current rating system, which happened under Reagan’s administration, has created similar problems for filmmakers over the years, and the composition and behavior of the MPAA is somewhat of a mystery to this day. Now, instead of preventing the creation of films, the MPAA takes whatever liberties it so chooses to ensure that any film labeled beyond an R gets as little theatrical distribution as possible, thus attempting to financially manipulate controversial films out of existence. The documentary This Film is Not Yet Rated explains this much better than I could, and I highly recommend it.

Sure, Kings Row is a movie with Ronald Reagan in it, but there’s one very important detail that’s ignored a majority of the time it comes up:

It’s actually a pretty good film.

It may be a Peyton Place-style melodrama, but it’s a fairly good one. The film follows several young people as they grow up in the town of Kings Row, and subsequently receive more than their fair share of hardships.

From here on, spoilers are inevitable.

Parris is an idealistic young boy of eight or nine with a name that only serves to confuse, especially since he disappears to Vienna later on in the film. He lives in the small town of Kings Row in the late 19th century, and has an innocent crush on one of his classmates, Cassandra Tower, who lives with her reclusive mother and stern, demanding father.

Parris and Cassandra spend an afternoon swimming naked in the river, and it’s painfully obvious that as little as possible is shown. We see Cassie’s back for a few seconds, just to have some kind of racy visual placeholder as we hear the two converse. Because the scene ends so abruptly, it’s rather strange when it comes up later, as we’re supposed to have some kind of memorable emotional attachment to it. Perhaps that would have been true in an era where showing a young girl’s back on film was frowned upon, but now, it just looks like a sad result of the Hays Code era. After a very sad turnout at Cassie’s birthday party, her father decides to pull her out of public school, and lock her away.

Reagan plays a wealthy, philandering upper-class orphan named Drake, and he takes Parris under his wing in an attempt to teach him how to be as obnoxious and unfaithful as Drake is. This doesn’t really take, and Parris remains innocent, unhealthily fixating on Cassandra Tower for the majority of his young life. Drake sets his sights on two other girls, Randy and Louise. Randy is a tomboy, literally from the wrong side of the tracks. Louise is from the “correct” side of the tracks, and her father is a well-known surgeon who doles out punishment to the wicked through malpractice, often refusing anesthetic to those he assesses to be inferior.

There’s a time jump to several years later, and adult Parris is studying to be a doctor. His beloved grandmother is ill with cancer, and when she passes away, Parris is stricken with grief for about five seconds.

He begins to study under Dr. Castle, Cassie’s father. Dr. Castle is a pioneer in his then-new field, psychiatry. Parris begins seeing Cassie in secret, and after using Drake’s house as a shag pad for several months, her behavior becomes even more erratic than before. One night, after Parris proposes and Cassie agrees to run away with him, Dr. Castle poisons her and then commits suicide.

Castle leaves his house and his fortune to Parris, along with a note explaining himself. Castle did not want Parris to make the same mistakes he did. Castle married young, and his wife was plagued by mental illness, causing her to isolate. He began to notice the same symptoms in Cassie at a young age, and that’s why he took her out of school. He did all of this in the name of “saving” Parris, a twisted perspective that isn’t treated with as much seriousness as one would imagine. Once Castle’s motivations are revealed, his actions are treated as a necessary evil, rather than a horrible atrocity.

Devastated, Parris retreats to Vienna to study psychiatry. The story then focuses on Drake and his two honeys, Louise and Randy. Louise’s parents take note of Drake’s love of the ladies, and forbid Louise to marry him. She refuses to defy her parents, and Drake begins riding past her house every day with a different girl in order to make her jealous. One of these unlucky women is Randy, who is finally able to get Drake to settle down and forget about Louise. Louise is devastated, and becomes a recluse, obsessing over Drake.

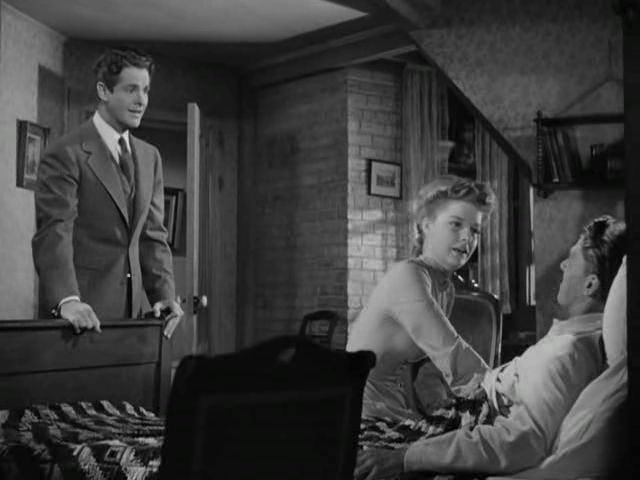

Drake loses his fortune due to a bank error that does not work in his favor, and is forced to do dirty peasant work on the railroad in order to make ends meet. One evening, his legs are injured in an accident. Unfortunately for him, his surgeon is Louise’s father, who decides that Drake’s legs are a lost cause and removes them. This prompts the famous line, “Where’s the rest of me?” Drake settles into his bed-ridden life with Randy as Parris prepares to visit Kings Row once more.

Upon his return, the two are overwhelmed with sexual feelings toward one another. Initially, Parris is bothered by Drake’s disfigurement, but soon finds that it impacts his sexual prowess very little. In fact, it makes for some very creative positions that Parris had never been able to explore in Vienna. Parris develops an amputee fetish, and quickly discovers that he is unable to maintain an erection with the ambulatory. His ticket to pound-town is only good for one now, and the couple escape to Vienna, where Parris removes his legs in a show of solidarity. They spend the rest of the film engaging in the raunchiest amputee orgies ever put to film, including multiple instances of tentacle penetration and a 30-minute sequence where Reagan vigorously strokes the barrel of a rifle until it misfires into his skull.

At least, that’s what rampant Ronald Reagan internet fanfic and the .gif above led me to believe.

When Parris is done making eyes at Drake, he runs into Louise, who is desperate to reveal the truth about her father. The good surgeon was angry with Drake, and decided to amputate his legs simply as an act of misguided divine judgment. She approaches her father about the truth, and he admits to this wrongdoing, threatening to confine her to a mental hospital if she ever came forward. After his death, Louise’s mother recruits Parris to treat her. Fearing Drake’s reaction, Parris threatens to send Louise to an institution.

Parris meets a woman named Elise, who’s been taking care of his house while he’s been away. Coincidentally, Elise is from Vienna, and she soon begins to take care of more than just his house. She advises Parris to tell Drake the truth about the nature of his disfigurement. Parris delivers a long-winded and silly speech in which he quotes Invictus. When he finally does so, Drake is suddenly healed of his deep malaise, and the movie ends abruptly on a frustratingly optimistic note that fits the tone of Kings Row about as well as I fit into a size two dress.

“Abrupt” is a great way to describe many of the major scenes in Kings Row. As we know from correspondence between Jack Warner and Joseph Breen, head of the Production Code Administration at the time, the adaptation of Kings Row was heavily advised against, and many compromises had to be made. It’s no wonder, because the book is a mean-spirited portrayal of Fulton, Missouri, the hometown of its author. The book focuses more on the sordid acts committed in “Kings Row” and the ways its citizens turn a blind eye. Here are some of the notably-omitted or partially-obscured plot points from the novel:

- As I sort-of mentioned before, Parris and Cassie get naked and swim in a creek during the portion of the story where they are both young children. We get a conversation that heavily implies that this is happening, and a brief shot of a girl’s back, but that’s it. Also, it’s an omitted character, Renee, who swims with Parris, not Cassie.

- There is a male character named Jamie in the novel, a friend of Parris. Jamie makes some very explicit sexual advances toward him, making their friendship quite awkward. It’s a good thing we still have Reagan to make eyes at Parris.

- In the book, Dr. Tower is definitely having sex with his daughter Cassie, and most likely kills her because he has impregnated her. He shoots her rather than poisoning her. It’s strongly hinted at in the film that Parris impregnated Cassie just before her death, an homage to this plot point.

- Dr. Gordon, Louise’s father, commits many more atrocities in the novel.

- The book is just a little more straight-up about all the fucking going on in Kings Row, and talks a bit more openly about the concept of nymphomania. It becomes very clear in the film that when characters go on “buggy rides,” they’re having sex. It’s the film’s version of those substitute words you use in front of children, once they’ve learned how to spell, to describe something not-so-family-friendly.

- In the novel, Parris cannot tolerate his grandmother’s suffering, and goes full Kevorkian. This mercy killing, along with his threats to commit Louise to an institution, mirrors the ways in which Parris is slowly becoming like Dr. Gordon and Dr. Tower, a rather sinister implication that you have to squint for a bit more in the film.

There was a right way and a wrong way to subvert the Hays Code during its reign. For example, a film like Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca was forced to conceal the implied homosexual relationship between Mrs. Danvers and Rebecca that Hitchcock wanted in his film. The already-creepy Danvers was made even more unsettling by some clever comments made to the protagonist about the deceased Rebecca’s clothing.

On the surface, this wasn’t grounds for lesbian Rebecca-Danvers fan theories, but Hitchcock portrays Danvers as masculine, overly jealous, and resentful of Rebecca’s replacement. In the context of the film, the lesbian undertones are obvious, but just obscure enough to make it past censors. It also never significantly distracts from the action of the film.

This sort of technique is one of the many reasons I love films of this era so much. Plenty is left to the imagination, and when it works in the film’s favor, it makes for a more interesting experience. In some cases, it created a need for films to be more respectful of its audience’s intellect in order to tell the story effectively, which lead to some really intriguing storytelling innovations.

For the most part, Kings Row deals with Hays Code restrictions in the wrong ways. To keep the film as morally above-board as possible, there are so many scenes that are cut short in order to avoid dwelling on the nastiness. This often left me wondering what the hell was happening, because these major events are incredibly rushed. For example, the idea that Cassie was pregnant with Parris’s child is conveyed by a character responding to an inquiry with, “I’ll tell you later.” This also affects the believability of character motivations and reactions.

Thankfully, many other aspects of the film make up for this. The score is very memorable, although I wonder how memorable it would be if I wasn’t comparing it to Star Wars’ score. At the Oscars, it was nominated for Best Picture, Best Cinematography, and Best Director. Rightfully, it lost all of those to Mrs. Miniver, but it’s still definitely nomination-worthy in all of those areas. The acting ranges from great to problematic, but even the worst performances in this film are entertaining, whether for the right reasons or not.

One major plot point and theme of the novel gets a bit buried in the film version, although it’s still present, and it makes this a pretty interesting watch in 2018. The film came out in 1942, and psychiatry was a more mainstream concept than it was when the film takes place. When Drake reads aloud a letter from Parris describing his chosen field of medicine, he is unable to pronounce the word “psychiatry” on multiple occasions. We hear about psychiatry as an abstract concept from several characters who try to describe Parris’s particular field of study. This is the film’s way of looking back at the turn of the century’s treatment of mental illness and saying, “look how far we’ve come.”

From a modern perspective, much of Kings Row’s treatment of mental illness now feels antiquated and potentially sexist. This is partially the result of watching a film about the advent of psychoanalysis that was made when psychoanalysis was still primitive by our current standards. The men in the film who experience the symptoms of mental illnesses and personality disorders are able to blend in, and their motivations are moral. Dr. Gordon seeks to punish sinners by subjecting them to dangerous and unnecessary medical procedures. Dr. Tower murders his daughter for fear that she may experience the crippling symptoms of mental illness, and while this isn’t exactly glorified, it’s portrayed as a somewhat sane explanation for his actions.

The women who show signs of mental illness are not treated so kindly. Betty Field’s performance as Cassie is almost campy, and she behaves hysterically every second she’s on screen. Her eyes bulge, and she’s seen frantically pacing around and talking at an abnormally fast pace. The same is true for Nancy Coleman (Louise) in the second half of the film, and there’s a fairly obvious parallel there. The men around them rarely seem to notice that there’s anything wrong with these characters, because, to quote Ronald Reagan’s Drake, “All girls act like that sometime.”

Treatment of mental illness aside, Kings Row is worth watching. It has a rich and fascinating history, and its melodramatic leanings ensure consistent entertainment. The film is a little hard to track down, but if you enjoy melodramas about the seedy underbelly of small-town life, this is a must-see.

7/10