As an absolutely rabid fan of cinema, I have a tendency to be incredibly long-winded when film is a topic of conversation in an informal setting. If that bothers you in any way, do not ever utter the words “Funny Games” in my presence – the result will likely be an alienating diatribe about the works of Michael Haneke, his unique approach to cinema, and particularly, the themes explored in Funny Games. This also occurs unprompted. If you’re one of my many victims, I apologize. I only ask that you understand my intentions were noble. Perhaps writing this entry will provide the catharsis necessary to finally hold my tongue. I make no promises.

We all have our “comfort movies” – those films you can put on at any given time and enjoy, no matter how often you’ve seen them. For the general public, these are usually comedies of some sort, or romantic dramas designed to moisten undergarments. If I had to pin down a few qualities that tend to determine how likely a film is to fit into this category, these would inevitably be: pacing, inoffensiveness, and levity. Some personal examples of “comfort movies” would be:

While you won’t see films like The Notebook or The Hangover on my list, those movies, along with anything that belongs to the Judd Apatow spectrum, are more typical examples of what I’m talking about. In the short list above, there are a few that overlap with my top ten favorite films, but not many. Upon returning home from an exhausting day, I’m not likely to throw on something overtly high-brow like Ingmar Bergman’s Persona, and I feel like that’s pretty typical even for a film buff.

In spite of this, I find myself revisiting Funny Games on a very regular basis. It’s not as if I’m noticing something completely new or revelatory on each watch, but I feel drawn to the film’s tongue-in-cheek nastiness and thinly-veiled hypocrisy. I imagine the director wagging his finger at me from beyond the screen as if to say, “You’re enjoying this aren’t you, you sick fuck!” Perhaps it’s a latent masochistic tendency that prompts me to continually relive this cinematic lecture and interpret that as “comfort”, or maybe I simply need a reminder that enjoying sadistic, mean-spirited entertainment is a little too socially acceptable in the modern landscape of media.

I imagine Michael Haneke as a miserable person with little faith in humanity. This is partly conjecture, however, over the course of the last 30 years, the Austrian director has graced us with some of the most uncompromisingly bleak works of cinema I’ve ever encountered. Also, just look at that face.

Many of his films thrive on the impact of horrific events that occur in the context of very slow, deliberately-paced stories. On a surface level, his work often feels very inconsequential and unsubstantial. Many of his plots are highly allegorical, and can tend to come across as preachy, pretentious, and at times even exploitative. While you can definitely classify his primary genre as “drama,” the major events depicted in his stories are often ones you’d typically associate with thrillers or even horror.

His first film, The Seventh Continent, is essentially 100 minutes of a family preparing for their own suicide – a decision motivated primarily by ennui. I think it’s fair to say that, generally speaking, watching a Haneke film is not usually a pleasant experience.

This does not sound like a ringing endorsement, however, it’s precisely these qualities that cause Haneke to stand out in the world of film.

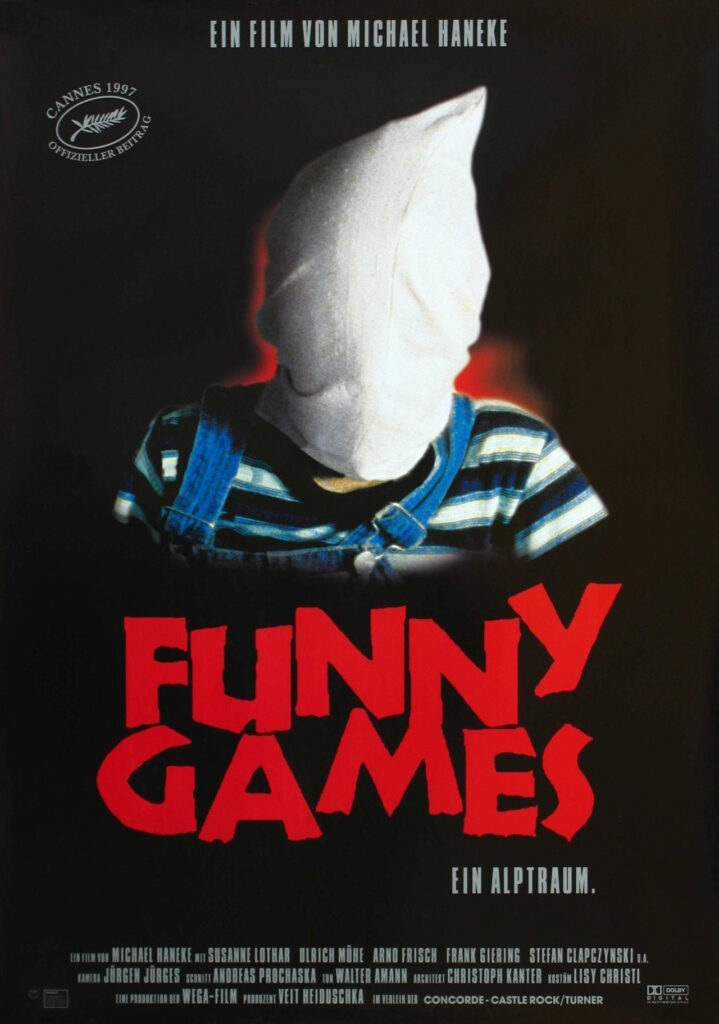

The 1997 version of Funny Games was the director’s fourth major film, after what he refers to as, “The Glaciation Trilogy,” which began with The Seventh Continent. The second entry is Benny’s Video, a film that receives far less attention than I believe it deserves, although this is true for most of Haneke’s work. The titular Benny is a sedate but otherwise relatively average 14-year-old boy with an affinity for violent media. He stumbles across a rather shocking video of a pig being killed with a bolt gun, and watches the footage on repeat. On his way home from browsing at his local video store, he meets a girl, and invites her to his home. He casually shows her the video, expressing his fascination. He then turns on his camera and murders her with a bolt gun. Benny is shockingly cavalier about this, and after stuffing the body in his closet, shows his parents the footage of the girl’s murder. They attempt to cover up their son’s transgression, but ultimately he confesses. When asked why he chose to come forward, his reply is a simple, “Because.”

The final film in this trilogy, 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance, feels quite different than the previous two. In concept, it’s somewhere between Rashomon and Magnolia. It involves several stories that converge at a single point – a botched bank robbery that ends in mass murder. As the title suggests, it consists of 71 sections, each of which sets up the climactic event, which is seen from each character’s perspective. Frankly, I don’t completely understand how this film fits in with the other two aside from just being slow-paced.

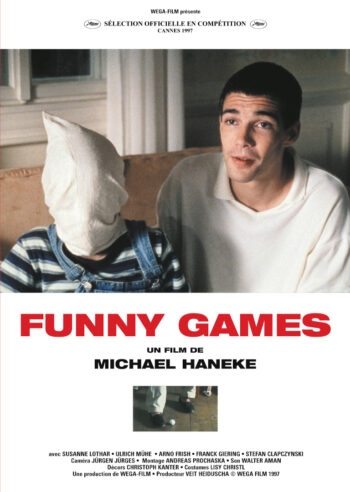

After the conclusion of this alleged trilogy, Haneke released the most notoriously divisive film of his career, Funny Games, in 1997. Reviews at the time were as polarizing as they come. For every glowing think piece touting the film as a masterpiece, there’s a scathing, angry review calling it one of the most disgusting and vile travesties ever put to celluloid. Even the overwhelmingly positive reviews don’t necessarily recommend seeing the film.

This is likely the kind of reception Haneke wanted and expected. Still, he felt the film never fully reached his target demographic – Americans. It certainly made an impact on cinema snobs and art-house geeks, but because the film was entirely in Austrian, it immediately alienated the average American film-goer, and had no chance of seeing a wide release stateside.

Having learned the hard way that Americans are seemingly allergic to subtitles, Haneke was frustrated that his cinematic sermon failed to resonate with the congregation he intended to didactically chastise. Nearly ten years later, he reached the conclusion that remaking the film in English was the only way his intended audience would be willing to sit through this experience, and Funny Games U.S. was born.

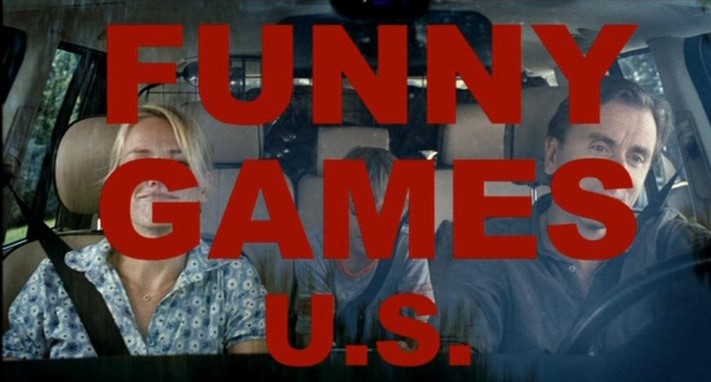

This new version is as faithful to the original as possible. It was intentionally re-cast with actors who would be far more familiar to American audiences in an attempt to capitalize on star power to lure in the unsuspecting. Naomi Watts and Tim Roth, both borderline household names, replaced Susanne Lother and Ulrich Mühe as the couple at the center of the film. The cruel fourth-wall-breaking duo, originally played by Arno Frisch (also in Benny’s Video) and Frank Giering, were replaced by Michael Pitt and Brady Corbet, both of whom have gone on star in or direct some of my favorite films of the last ten years, although they were less known in 2007.

Haneke went as far as to film the entire project in sequence, and the final product is extremely close to being shot-for-shot identical to the 1997 version. The original set was meticulously reconstructed as well, with a special effort to maintain the same scale. The goal was to re-create Funny Games so faithfully that the only fundamental differences would be the actors and the spoken language. In that regard, this remake is exceptionally successful.

In order to really break down the central themes of Funny Games, I have to veer into spoiler territory for a while. This isn’t necessarily a story that suffers greatly from spoilers, but I plan to delve deep here, and out of respect for those who wish to experience it without prior knowledge, here is your spoiler warning.

Ann and George are a couple on their way to their vacation home with their dog and young son, Georgie. We get a glimpse of what we’re in for as the family drive down the highway while playing a game of “guess that classical piece.” Midway through this scene, the classical music shifts abruptly to a blend of two songs by the thrash-jazz band Naked City, full of screaming and aggressive instrumentation. It’s an apt juxtaposition, and it sets the mood beautifully.

Before reaching their destination, they stop briefly at the home of a neighboring family they plan to challenge in golf the following day. Immediately they notice two strangers in white golf outfits with the family, and after a short and rather odd conversation that puts Ann and George a little on edge, they arrive at their vacation home and begin preparing for a pleasant and stereotypically-bourgeois getaway.

While George and his son set up their sailboat, Ann begins cooking dinner. She is interrupted when Georgie appears to inform her that there’s someone at the door. She is greeted by the shy and aloof Peter, who claims to have been sent over by the neighbors to borrow some eggs. During the process of obtaining these eggs, Peter accidentally pushes Ann’s cell phone into a sink full of water, and then drops the eggs on the floor. Once the mess is cleaned up, Peter awkwardly asks Ann for more eggs. She becomes incredibly frustrated with Peter’s subtle mind games, but sends him on his way with another set of eggs regardless.

As Peter exits, the family dog is heard barking off-screen, and Peter returns with his identically-dressed friend Paul to inform Ann that the dog had caused Peter to drop the eggs once more. Paul shows a strange enthusiasm regarding a set of golf clubs in the corner, and asks to borrow a driver and a ball to try them out. By this time, Ann is furious, and George and Georgie return to a rather confusing scenario after hearing a strange yelp from their dog, followed by silence. As Paul tries to explain the situation in a subtly condescending way, Ann asks George to get rid of the two young men. Wanting to support his wife, he attempts to get rid of them peacefully. Instead, Paul grabs the driver and whacks George violently in the knee, and the family finally begins to understand that this is a hostage situation.

Ann attempts to reason with Peter and Paul, and then points out that the two will surely be caught. The family gradually begins to realize that Peter and Paul have covered their bases quite comprehensively, ensuring that none of their actions have any repercussions. The family next door, who were possibly going to join them for dinner, were the previous victims of the two young men. The only phone in the house is the cell phone that Peter quite deliberately dropped in the sink. The only person potentially strong enough to overtake the two by force, George, is now crippled. They are now fully at the mercy of Peter and Paul.

A family who live across the water arrive via sailboat, and Ann is sent out to greet them, Paul just behind her. She introduces him as a friend of their closer neighbors, and tries her best to ask them for help without repercussion from Paul. She is unsuccessful, and they sail away.

After returning to the house, Paul proposes a guessing game to lighten the mood, and this is where the titular “funny games” begin. He reaches into his pocket and pulls out a golf ball, asking, “Why do I have this ball?” The family resists playing the game, and when they do, George is further assaulted. Now frightened enough to play along, Paul guides them through the game. He previously asked to test out a golf club, and while he went outside very briefly to do so, the ball remained in his pocket. The family solve the riddle with Paul’s help, only to realize that he used the golf club to beat their dog to death.

Ann asks where the body is, and in order to find it, Paul forces her to play a game of hot/cold. As he casually calls out “warmer” and “colder,” he turns to face the camera and grins at the audience. The game leads Ann to the back of their SUV, and as she opens the back hatch, the deceased dog drops to the ground.

Back at the house, the group meet in the living room. Paul explains that there is no way out of this situation, and he proposes a rather arbitrary bet to the family. Peter and Paul bet that by 9:00am the following morning, all three family members will be dead. They’re fairly unresponsive to the duo’s request, so Paul makes the counter-bet on their behalf – that the family will survive the night. Ann, tired and angry, asks why they won’t just kill the family and get it over with. Peter giggles and grins, replying, “You shouldn’t forget the importance of entertainment.”

The young men then begin gleefully taunting the family. Paul creates a sad backstory about what lead Peter to a life of crime, claiming that he’s been traumatized by a partially-consensual sexual relationship with his own mother. Peter cries, playing along, but soon begins laughing as Paul reveals that the story was a fabrication, as was every other reference to Peter’s origins. Paul implies that they’re simply privileged youth who have nothing better to do than entertain us, the audience, with creatively-constructed torture and murder.

The conversation then shifts to Ann’s body. Peter and Paul argue over whether or not Ann has saggy breasts and “jelly rolls” at her age. Unable to agree definitively due to the presence of clothing, Paul proposes the next game, Cat-In-A-Bag. He grabs a pillow case and puts it over young Georgie’s head with excessive force, explaining that it would be improper for their innocent son to be subjected to seeing his mother naked.

“Now the cat is in the bag, let’s see if mommy’s titties sag!”

Ann is forced to strip, and once the two are satisfied that she is indeed as fit as Paul suspected, she is allowed to put her underwear back on, and Georgie is released. Taking advantage of this opportunity, the boy escapes and enters the neighbor’s house to ask for help, but only finds their dead bodies. Paul and Georgie play a game of cat-and-mouse in the abandoned house, and the boy eventually finds a shotgun. Georgie threatens to shoot Paul if he comes any closer, but Paul advances toward him regardless, smiling. He asks Georgie to pull the trigger, and when he finally musters up the courage to do so, the empty shotgun clicks as Paul pulls two shotgun shells out of his pocket. Georgie is taken back to the house.

Paul tells Peter to count Eeny, Meeny, Miny, Moe-style, and then shoot the loser. They bicker for a while about the logistics of this, and how to properly count in order to ensure randomness. During this process, Georgie attempts to flee again, and is shot by default. As George and Ann scream and cry, Peter and Paul casually leave the house. Over the course of a very, very long static shot, we see Ann grieve and then free herself from her restraints. The couple decide that George should stay at the house and try to get the cell phone to work, and Ann should flee for help. She makes it to the road, seeing a van off in the distance and flagging it down, unaware that Peter and Paul are inside. She is apprehended and brought back home for one final game.

It is determined that George will be the next victim. Paul’s next game is The Loving Wife, or rather, “Whether by knife or whether by gun, losing your life can sometimes be fun!” Ann is forced to recite a prayer from memory, and if she recites it perfectly, she gets to choose which weapon should be used and potentially sacrifice herself to save George. Ann again pleads with them to just get it over with, and this perturbs Paul. He scolds her for not playing along, and addresses the audience.

Unable to make the decision, George is stabbed, and Ann reaches for the shotgun, killing Peter. Paul becomes irritated, and frantically begins searching for the TV remote. He then hits the rewind button, and the previous scene plays backwards until just before Ann grabs the gun. Paul retrieves it from her, and once again scolds her for breaking the rules, killing George.

The young men bound and gag Ann, and take her for a morning boat ride. They have a seemingly unrelated conversation about what seems to be a book that Peter has read recently. Ann tries to grab a knife that was left in the boat earlier in the film, but Paul notices, and her last chance at freedom is thwarted. The young men notice that it’s almost 8:00, so Paul decides to end the game by pushing Ann of the boat and into the water. Peter asks why he did this when she had an hour left, and he replies, “It’s too difficult to sail like this, first of all. Second of all…I’m getting kind of hungry.”

They sail across the bay to the house of family that sailed by in the first half of the film. Peter knocks on the door, and explains that Ann has sent him over to borrow some eggs. When he receives permission to enter, he smiles knowingly at the camera, implying that the cycle will continue, and we once again hear the Naked City mash-up as the credits roll over Paul’s face.

As you can probably imagine by now, much of Funny Games is difficult to sit through, especially because of how convincing the acting is. Susanne Lother, the mother in the first film, did an incredible job of looking pathetic and downtrodden for most of the film. Naomi Watts, on the other hand, completely one-ups her in my opinion. With the opening egg scene, the way she begs and pleads with her captors, and the seven/eight-minute grieving scene, her performance is exceptionally nuanced, and it’s exactly what I would expect from Watts. Lother tended to look a tad more pathetic in the original, but most of that was due to lower lighting.

Tim Roth as George is also great, and frankly I thought Ulrich Mühe was one of the weaker players in the original. Arno Frisch as the playful yet menacing Paul was also great in 1997…but Michael Pitt in this remake is so strangely likeable. Brady Corbet’s interpretation of Peter adds an extremely sleazy element to his character, and his inappropriate smiles and giggles become gradually more chilling as the film goes on. In both films, the child of the couple is played competently, but I prefer Devon Gearhart’s performance in the 2007 version immensely, because that kid has a face that really needs punching, especially when his lip quivers.

The acting in this version further accentuates a strange paradox in the first film. Peter and Paul are written in a way that feels a bit like the stereotypical villains found in many Hollywood films, and at the same time are a reaction to that particular trope. A villain should be, by American standards, relatable to the audience in some way, and often snarky and entertaining enough that the audience has a difficult time truly choosing sides. This is usually to create a perceived layer of moral ambiguity. The problem that Funny Games points out with this style is that while a complex villain can be a source of entertainment, writers often create a scenario where the villain is so likeable that we forget these people are usually straight-up murderers, or at least engage in some kind of morally reprehensible actions. This is, after all, what makes them the villain of the story.

Peter and Paul are barely villains by that standard. Hell, they’re barely even characters. They address the audience on a frequent basis, explain what twisted deeds they’re about to engage in, and have casual conversations throughout the story that rarely have much to do with what has recently happened on-screen, at least on a surface level. They are also meticulously in control of the events of the film to a god-like degree. Their backstories and names clearly don’t matter either, as they change frequently throughout the film. Peter and Paul, Tom and Jerry, Beavis and Butthead – these names matter as little as whether or not Peter is actually a med student, a victim of incest, or “fat” white trash. They are our guides through this journey rather than typical villains, and while they’re busy taunting Ann, George and Georgie, they’re also channeling their charisma to dare the audience to allow themselves to become complicit in the on-screen crimes by acknowledging the humor at play.

You can tell quite a bit about how desensitized someone is to violence in media by when they stop feeling any shred of fondness for Paul and Peter, at least this is the intended litmus test. The acts that occur on-screen are nearly unspeakable, and while we’re constantly seeing evidence of the terror being inflicted through the family’s reactions, it’s nonetheless quite difficult not to grin, chuckle, or maybe just groan at the cliché nature of it all when Paul first addresses the camera. Haneke is poking and prodding to find your breaking point – that moment when Paul’s charisma becomes vile and sickening rather than oddly amusing – and this is represented by the way each event escalates. For many American audiences, this will either happen immediately, or directly after the 8-minute grieving scene meant to act as your final wake-up call.

For the sake of analysis, we’ll call the first game:

The Egg Game

No matter how pissed off one is at Funny Games as a film, it must be acknowledged that the first major encounter with Paul and Peter is a rather impressive concept. Peter innocently knocks on the door asking for four eggs, and while doing so feels out Ann’s personality and the family’s level of isolation, gauging her reaction to his clumsy-but-deliberate attempt to disable her phone. While trying to convince Ann to replace the four eggs he broke the first time, Peter is careful to use verbiage that draws out information such as whether or not the family is really expecting company, the nature of the family dynamics in the house (is George a threat, for example), as well as the limits of Ann’s kindness and patience.

When Peter breaks the eggs for the final time, he is careful to do so in a way that will both invite Paul into the scenario, and create a situation where it’s very difficult to blame him for the accident. The family’s dog, Lucky, is somewhat culpable, having jumped up and knocked the eggs out of Peter’s hands according to Paul. Peter conveniently has a fear of dogs, and Paul is there to rescue him, acknowledging that sending him over alone was a bad idea in the first place.

With all these things in place, the pair is ready when the patriarch finally arrives. George walks into a rather difficult-to-explain situation, and at the very least it’s a story that Ann is unable to quickly recount in order to justify her indignation to her husband. When George doesn’t respond precisely the way Ann wants him to, she storms off, leaving him to deal with Peter and Paul, frustrated that he didn’t simply take her emotional reaction at face value and immediately eject them from the premises. We’ll get back to that.

Anywhere else, this setup would be the mark of two seasoned criminals who have probably been incarcerated for some time, but because Peter and Paul are young, sterile in appearance, and hardly characters, the scene demonstrates their god-like level of manipulation, ensuring that the audience understands these aren’t two ordinary men who will get their comeuppance in the end, and setting up just how hopeless the situation is. In a way, it’s deliberately designed to be predictable. You know that Peter and Paul will inevitably torture this family to death from a fairly early point in the film, and yet you’re still watching.

The Second Game:

Why Do I Have This Ball?

When Paul first tries to use the idea of games to torture the family, neither the characters nor the audience are fully aware of what Paul and Peter are capable of, and therefore they refuse to take his game seriously until Peter resorts to physical violence. Once the family are aware that Lucky is deceased, it is Ann who is chosen to engage in the hot/cold mini-game, rather than George or Georgie. George wasn’t exactly very ambulatory at the time, making him a poor choice, but Georgie would likely have been even more traumatized than Ann to see the family dog fall out of the back of their SUV.

This is the first major example of any “positive” trait in the young men aside from awkward charisma. In America, it’s really not uncommon for parents to shield their children from on-screen violence, but conceptually it’s completely A-Okay. For most of the film, until Georgie tries resisting and ultimately runs away, he is more of a passive participant in the games than his parents. Paul and Peter joke around with him and tease him a bit, while also treating him as something of a servant when Peter demands that Georgie make him a sandwich. Their treatment of him represents a fairly typical American stance on child-rearing, and yet Georgie is still around for much of the film, experiencing just as much terror as his parents regardless of how much he actually sees with his own eyes.

The Third Game:

Cat-In-The-Bag

The game that inspired the cover of the 1997 version is probably the most easily-interpreted aspect of the entire movie. At this point, everyone in the family has been exposed to the effects of playfully-violent torture, and yet when Ann is forced to strip in order to settle a petty dispute between Paul and Peter, the pair insist that Georgie wear a pillow case over his head in order to protect him from the “savagery” of his own mother’s nudity. This perspective has been a popular subject of scrutiny when it comes to American culture, especially when contrasted with European culture. It doesn’t take much to understand the contradictory nature of freaking out when a child is exposed to a naked body, and turning a blind eye to a decapitation, so long as it’s not real.

This also addresses a major criticism of Funny Games as a whole: if Haneke is chastising the audience for being resigned to on-screen violence, doesn’t that imply censorship is the answer? The cat-in-the-bag scene says no. As addressed before, the fact that Georgie is unable to see the terrifying events in this case is completely moot, as it’s traumatizing regardless. Georgie also struggles quite a bit when the pillow case is first put on his head until it’s finally pointed out that struggling will only make it more difficult for him to breath. In my opinion, understanding this scene is crucial to the message of the entire film, because the outcome of Peter and Paul’s version of censorship is still cruel and disgusting. Nothing about stuffing a child’s head in a pillow case yields positive results. This idea is also further explored in Michael Haneke’s essay, “Violence + Media”, which I’m assuming he felt obligated to write in order to avoid being a poster child for censorship.

The Fourth Game:

Cat-and-Mouse

When Georgie is finally able to make a run for the neighbor’s house, we’re able to see how these events have affected him from his own standpoint. Just as the boy reaches the house and is about to breath a long sigh of relief that not all hope is lost, he discovers the dead bodies of his neighbors, literally scaring the piss out of him. Instead of running around with a dark spot on his pants, he makes the logical decision to take off his soaked jeans and spends the rest of the film in his underwear. Perhaps this is a bit of a stretch, but I see this as reactionary to the cat-in-the-bag sequence. Georgie removes his pants without a second thought, and makes no effort to find new ones, something that most characters immediately do after pissing themselves. However, this is a life-or-death scenario, and Georgie isn’t exactly thinking about how silly he looks in his undergarments, and to me that makes perfect sense. It’s not enough to alter his fate, but it was probably his best shot at making it through the night. Georgie gave zero shits about his own indecent exposure, further supporting the absurdity of the issue confronted with cat-in-the-bag.

This is also the first time we see Paul do something nearly impossible on-screen. He’s able to track Georgie through the entire house, place the shotgun without bullets in an opportune place, ensure that the boy will never know his current location by playing loud music, and keep him in the house through clever placement of all of these elements. In this case, it initially feels like bad, predictable writing until you’ve fully acclimated to what Paul represents. These are all very convenient events, and that sort of convenience is something often complained about in horror films.

The Fifth Game:

Eeny, Meeny, Miny, Moe

Perhaps being a bit exhausted from the previous excursion, Paul and Peter seem to have grown tired and bored of their own games, and resort to a fairly uninteresting method of picking their next victim. Paul leaves the room to make a sandwich, asking the family casually if there’s anything they need from the kitchen. A gunshot is heard and Paul looks up for a brief second before continuing his culinary endeavor. We hear Ann and George’s screams, and end up watching NASCAR on the blood-stained television for a rather lengthy period of time as Paul gets caught up in the minutiae of “Eeny, Meeny…”, scolding Peter for “having no sense of timing.”

In spite of how brutal Funny Games has been up to this point, this is actually the first murder that occurs in the story-line, and it’s not even on-screen. The camera is instead pointed at Paul, whose utter lack of reaction is somewhat shocking, though by now it shouldn’t be. For a film that has a reputation for being sick and twisted torture-porn, it’s notable that so much of the violence is off-screen, especially Georgie’s murder. The death of a child is almost always tragic in American film, in spite of the fact that adults die on a fairly regular basis, often in brutal ways. This scene is less about pointing out any sort of double-standard (because the death of a child IS horrible and unthinkable), and more about mirroring the conventions of modern cinema.

When death occurs in film, the audience is rarely expected to grieve in a realistic way, or even given the space for such emotions. Haneke now tortures the audience in a different way by forcing us to confront the consequences of what we just watched unfold.

Peter and Paul leave, casually thanking the family for use of their golf club, while the camera focuses on a television covered in Georgie’s blood. This serves as a visual metaphor for the entire film, again chastising the audience for being content with lazy, boring entertainment (NASCAR) in spite of the consequences (Georgie’s blood.) I really wish this was a giant middle finger to NASCAR itself, and if you really suspect that Haneke is a vile human being, perhaps the message is that those who watch NASCAR should be shot in their sterile living rooms. This isn’t the case, and drawing a parallel between racing and a child’s death is probably missing the point…and being an asshole. NASCAR is chosen for two very simple reasons: It’s extremely American, and it’s notoriously boring.

However, subjecting us to NASCAR isn’t enough for Haneke. After Peter and Paul leave, and we’ve stared at the television for a while, we see a shot of the living room that goes on for about 7-8 minutes. The race is still playing on the television, with Georgie’s dead body next to it. At the center is Ann in her bra and panties, her hands and feet bound, and we watch as she slowly hops around looking for a way to free herself from her restraints, taking cry breaks in between. Once free, she rushes to George, and the two grieve audibly. This process takes so long that the film once again begins to feel gratuitous, but as I pointed out before, the consequences of death and grief are rarely seen on-screen, and here it’s happening in real time. The central thesis of this single shot is that violence has real consequences, and by integrating it into film as a comedic element or through the death of an extra that nobody cares about, the audience isn’t seeing the full picture. They’re being robbed of the opportunity to grieve for a character they’re supposed to have formed a relationship with on some level, and as such, the typical on-screen death becomes absurd and even comic. Haneke is repairing that disconnection by finally showing the audience something truly grotesque, but not through the violent visuals it appears the rest of the film is leading up to.

The Sixth Game:

False Hope

Once Paul and Peter leave, George and Ann have to pull it together in order to survive, and it seems that there may be hope after all. By now, we should know better, and so should the characters, but they try to call for help regardless. It’s not that Ann and George do anything illogical or frustratingly naïve, and during this sequence, it really does feel like Ann has a chance to escape.

The audience is given false hope as well. George apologizes to Ann before she leaves, obviously feeling that he’s failed the family by allowing this to happen. Ann kisses him, assuring him that he’s not to blame. The death of Georgie feels like a very climactic event, and in most home invasion thrillers, this is the sort of scenario that would normally cause the assailant to make a fatal mistake, triggering a third act in which Ann gets her revenge. Instead, she is apprehended, and their hopeless situation becomes apparent to George when a single golf ball rolls slowly down the hallway and into view. There’s almost a look of relief on his face, and both he and Ann appear completely resigned to their own fate.

The Seventh Game:

The Loving Wife

One of the themes that often gets buried in the film’s commentary on violence involves the shame associated with George’s inability to help the family from the very start. George is supposed to be the head of the house, and he should be in control of the situation – the story’s savior. Even before things truly escalate, Ann expresses numerous times that she feels he’s too passive, and there’s clearly a little tension in their marriage because of this.

Paul informs Ann that it’s George’s time to die – unless she’s willing to step in for him. She forgave George immediately after Peter and Paul left the scene, but that was when there was still hope. Now that she’s tied up, terrified, and just waiting for it all to end, she doesn’t even seem to consider stepping in for George.

Ann is now forced to say a prayer to prove that, “God is on her side.” If she can recite it perfectly, she gets to choose how her husband will die. However, she expresses that she doesn’t know any prayers, and Peter suggests a very short one for her: “I love you God with all my might. Keep me safe all through the night.” When she first recites it, she does so in a very quiet manner, and this angers Paul. He wants to hear some conviction in her tone, and reminds her that she’s pleading to God for salvation. However, in the context of Funny Games, there is no God, only Paul and Peter. She is essentially pleading to him, and Paul is just finding the most humiliating way to go about that, for the sake of entertainment. Paul points out that the person she’s praying to is “up there,” but when she delivers the prayer, she is facing Paul. Once she is successful, Paul asks her to do it again, only this time, backwards. She sees a window of opportunity and grabs the shotgun, killing Peter. This is the beginning of the satisfying climax we’ve been lead to believe is yet to come.

Paul is furious with Ann, and shouts, “Where’s the fucking remote control!” He presses the rewind button (actually, it’s the volume down button…this has bothered me for years) and the last scene plays backwards until the point where Paul introduces the game. This time, when Ann grabs for the gun, Paul stops her and complains that she has tried to cheat, prompting him to finally kill George. This is the final nail in Ann’s coffin, and the most God-like act any character can ever commit – the manipulation of the outcome of the film they’re currently in.

The Boat

After Ann is finally on the boat with Paul and Peter, she finds the knife that was accidentally left in the boat at the beginning of the film, and tries to untie herself. Paul notices, and congratulates her on her “Olympic spirit” before pushing her off the boat, and all hope is lost. The actions in this scene that involve Ann are very brief, and they occur while Peter is trying to recount the plot of a film he once saw. For those who haven’t fully comprehended why this film exists in the first place, this is a crucial conversation, and parts of it are mixed low enough that it’s barely audible. When any talk of Ann is removed, the transcript looks like this:

Peter: “So everything is its mirror image. But of course. all these predictions are lies to avoid panic. Now Kelvin knows what’s going on. He wants to warn his wife and daughter in time. The problem isn’t only how to escape the anti-material world, but also how to communicate between the two worlds. Finally there’s a gap-“

[A literal gap occurs, and Ann is dumped in the water.]

Peter: “It’s like you’re inside of a black hole. The gravitational force is so great that nothing, absolutely nothing can escape. Which means absolutely no communication. But Kelvin has this-“

[Peter asks why Paul ended the game so quickly, then continues talking.]

Peter: “And when he overcomes the gravitational forces, it turns out that one universe is real and the other one is fiction.”

Paul: “How?”

Peter: “How do I know? It’s a kind of model projection in cyberspace.”

Paul: “Okay. so where’s your hero now? Is he in reality or is he in fiction?”

Peter: “His family’s in reality, and he’s in fiction.”

Paul: “But isn’t fiction real?”

Peter: “Why?”

Paul: “Well, you can see it in the movie, right?”

Peter: “Of course.”

Paul: “Well, then it’s just as real as reality, because you can see it too. right?”

Peter: “Bullshit.”

Paul: “Why?”

The conversation is interrupted by their arrival at the next house, but these characters have said all they need to. In this metaphorical story, a man named Kelvin is sucked into a black hole and lands in a fictional alternate reality. He tries to warn his family in the real world of a vague threat, but is unable to because he’s trapped in a fictional realm that cannot communicate with reality. At least, this is how Peter sees it.

Paul makes the counterargument that if you can see it, it’s as real as reality. This final disturbing notion reveals his perspective on the events in the film. You have just watched two young men torture and murder a family, and you did it for the sake of entertainment. The family are caught in their own fictional universe. As is implied by the second gap in conversation, the family found a means to escape. They’ve fled to your own living room, where you watched Paul make a sandwich while Peter shot a 10-year-old boy in the face. You knew the entire time that this was inevitable – that the family was trapped in a black hole from which they can never escape, but you did nothing to stop it. You could have grabbed your remote and rewound the film, or even shut it off entirely, but you didn’t.

Their blood is on your hands.

As a film that ultimately indicts its own audience for the violence inflicted on its characters, it’s no wonder Funny Games was extremely divisive, but the remake is even more so. The big problem is that those art-house geeks and film buffs who saw the first one are still the demographic most likely to watch this movie. Without considering Haneke’s intent, it’s pretty easy to see why American audiences were puzzled by why this film was remade in the first place. To make matters worse, it’s such a nasty and unpleasant film to watch that anyone who had seen the previous one was unlikely to watch this. Still, watching it with a critical eye and the proper context, it’s one of the most rewarding viewing experiences imaginable. Funny Games is so densely and deliberately crafted that if one is primarily concerned with the quality of a film, it’s almost the perfect movie.

Throughout much of my life, I have proclaimed American Beauty as my favorite film. It’s great, for sure, but it’s not the kind of movie to prompt an excruciatingly long analysis like this one. For this reason, Funny Games is my true favorite film. During the composition of this piece, I watched it another three times, and I’m sure I’ll watch it a hundred more if I live long enough to do so. It is my comfort movie, not because it’s comforting (and it certainly isn’t), but because the answer to the question, “Do you feel like watching Funny Games?” will always be met with an enthusiastic, “Yes!” due to my love of deconstruction.

If you’re intrigued by what you’ve read, go see the movie. If you’ve seen it previously and it really didn’t resonate with you, watch it again with the director’s intent in mind. It’s worth it.