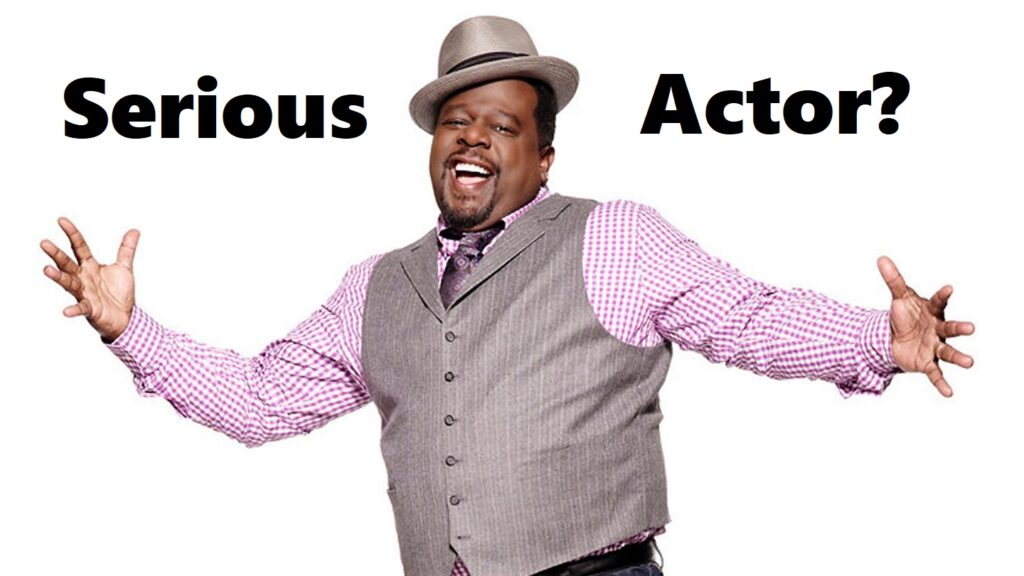

First Reformed looks horribly boring. Its posters mostly consist of Ethan Hawke’s face. Hawke himself is an actor that has always had more misses than hits in my opinion, but realistically, most of his performances can be described as “fine.” It’s a movie about church. It’s directed by Paul Schrader, who’s been in a pretty significant slump as a director for some time, having far more success as a writer. Worst of all, Cedric the Entertainer is in this movie. These factors all point to First Reformed being a rather boring, forgettable film.

This is a shame, because First Reformed is one of my favorite films of 2018 so far. I fear that, for the aforementioned reasons, this is going to fly under the radar and be forgotten, in spite of the critics who have been cheering it on for several months now. We’ll likely have another Personal Shopper scenario on our hands, because nobody listens to critics.

*sigh*

Don’t let these first impressions fool you. First Reformed is a little slow, but it’s definitely not an uneventful film, and it’s not the predictable drama it appears to be, so let’s get that out of the way.

Taking a few steps back here, there’s another movie about a priest that immediately came to mind about 20 minutes into the film: Ingmar Bergman’s Winter Light. In fact, 2/3 of this movie is almost a beat-for-beat remake, to a shocking degree.

Winter Light has never been my favorite Bergman film, but it’s one that I have a deep connection with for a variety of reasons. It’s the second in Bergman’s unofficial “faith” trilogy, and it explores a rural priest’s existential crisis. On my first watch, I was sitting up in bed, fully engaged and excited to see yet another acclaimed Bergman film. It’s in Swedish of course, so there were subtitles.

As I watched pastor Tomas struggle with his frustration at the silence of God, I saw much of myself in this character. I was raised in a Nazarene church, and made the decision fairly early on that religion was not something I was likely to pursue later on in life, but due to certain circumstances, I was forced to push those doubts aside and keep up appearances. I engaged in the Bible trivia competitions set up by our denomination, I regularly attended our district assembly, I worked to increase the attendance of our church’s youth group, and while I certainly had some strange, at-the-time-unexplainable behavioral issues, I was seen as moderately pious for a young person. Coming from a family with quite a few pastors, I wasn’t about to soil their reputations by revealing that I wasn’t wholly invested in the idea of a higher power, and, specifically, the idea of my particular denomination’s higher power. Just like pastor Tomas, I was a cynic in a position that prevented me from revealing my cynicism and doubt.

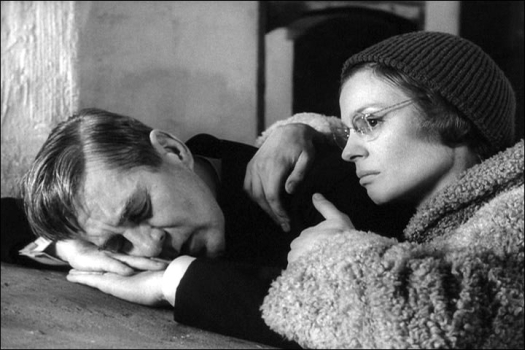

Throughout the film, its subtitles became harder and harder for me to read, and by the end, I had lost the right half of my vision almost completely. Because I was so invested in the philosophy and theology at play in Winter Light, I didn’t fully consider the severity of my vision issues. When the film was over, I of course began to panic, and less than a week later I was diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis. During Winter Light’s run-time, my immune system had decided to attack a portion of my optic nerve. Some of that vision, but not all, eventually returned, and while the diagnosis was initially traumatizing, I’m now grateful to have a solid explanation as to why I’ve always been rather sickly, and more importantly, I’m thankful that I’m not entirely a hypochondriac. My life has ultimately been better post-diagnosis. Still, I have not been able to watch Winter Light again until very recently. The following is what I see when I stare directly at this character’s nose:

During the diagnosis process, the film was on my mind quite often. I thought about it in hospital waiting rooms. I thought about it in the MRI machine. I thought about it while large doses of the steroid SoluMedrol were being pumped directly into my heart for hours at a time. I thought about it while a host of nurses and phlebotomists frantically tried to start an IV in various parts of my body and failed over ten times as I begged them to keep trying, until they reached a limit where to continue would probably have been unethical.

Winter Light is not exactly an uplifting film, and its subject matter is rather weighty. In spite of this, its complex issues were a welcome mental distraction, and it was an essential ingredient in getting through the diagnosis process. If it were not for Bergman and a host of supportive friends and family, I may not have made it through that process, and to them, I will be forever grateful.

But enough about MS. What makes Winter Light so fantastic?

*spoilers for Winter Light, if you care (and you shouldn’t)*

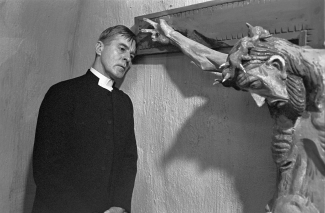

Tomas Ericsson is the pastor of a very small church, with only a few members. His town has fallen on hard times, and its residents don’t attend like they used to. This leaves Tomas feeling obsolete and frustrated. He’s sick with what we’re told is a cold, and he’s still grieving the loss of his beloved wife. Jonas and his pregnant wife Karin approach him for advice. Jonas has been rather depressed lately, in part due to his guilt over bringing a child into this war-torn world, and in part because of his entirely-founded fear of a nuclear attack from China. Jonas begins asking the “hard questions”, and in frustration over his inability to provide any clear answers as to why a loving god would allow this scenario to happen, Tomas tells Jonas to come back later.

We find out that the teacher, Marta, has been having an affair with Tomas for quite some time, but both decided to sever the relationship for different reasons. Marta consoles the ailing Tomas, and he relays his inability to help Jonas. Tomas is beginning to lose his faith, and therefore cannot provide the kind of counsel Jonas was looking for. Through both conversation and a hand-written letter, Marta explains to Tomas that she still loves him, but that he isn’t capable of reciprocating that love because of his guilt over their out-of-wedlock relationship, his disgust at a vaguely-described rash on her body, and his unquestioning love of God.

After Tomas passes out for a while, Jonas arrives at the church for some advice. This time however, Tomas is unable to keep up the façade. He speaks of how selfish his faith was, how he joined the clergy to be closer to God, to be one of His favorites. He talks about his time serving in the Spanish Civil War, and all of the atrocities he witnessed. This brings him back to the question of, “How could a loving God allow this to happen?” During the war, Tomas was too pious to ask this question, so he ignored it entirely in favor of the egoistic comfort provided by blind faith. Tomas’s main point to Jonas is that life makes a hell-of-a-lot more sense if we deny the existence of God entirely. Without God, we no longer have to question His relationship with the human suffering and cruelty that surrounds us, nor do we have to question His silence. This is a revelation for Tomas, and he appears at the same time angry and ecstatic at reaching this conclusion. After Jonas leaves defeated, Tomas confronts the crucifix, declaring himself free from the bondage of belief.

Unfortunately, this was not the answer Jonas was looking for. Jonas came to Tomas for comfort, and the conclusion that there is no God does not provide him with the same sense of relief as Tomas. Marta, who’s been eavesdropping on Tomas’s monologue, reveals herself and embraces him, expressing her joy as he is now free from the bondage of faith. Tomas is cold to her advances, and cannot help but wonder if he provided solid counsel to Jonas.

“So [Jonas] . . . went away and [shot] himself.”

– Matthew 27:5, NIBT (New International Bergman Translation)

Tomas and Marta’s exchange is interrupted with this shocking news. He arrives at the scene and helps the police cover up Jonas’s body. Once again, Tomas is feeling ill, and he drives with Marta to her home.

After she supplies him with comfort and medicine, Tomas lashes out at her, trying to explain his resentment toward her by any means necessary. Tomas grew tired of the town gossiping about their controversial affair. This does not shake Marta. In a frustratingly cruel attempt to alienate the caring woman, he delivers a diatribe about every little aspect of Marta’s existence that offends him. She’s always blabbering away about her petty problems, attempting to care for Tomas when he doesn’t want to be cared for, and most importantly, she can never measure up to his late wife. His deceased partner was the only woman he ever truly loved, and in spite of Marta’s affections, he can never bring himself to love her in the same way.

Tomas must now make a stop at the home of Jonas’s widow and children, and in spite of having been humiliated by his recent comments, Marta agrees to drive him. When they arrive, the widow Karin expresses her sorrow. She is stricken with grief, but more than that, she fears for the survival of herself and her children. She seeks comfort from Tomas, but he is unable to provide any. He finds himself speechless, and leaves after making a vague and disingenuous offer to help the widow and her family.

Tomas and Marta return to the church, as there is supposed to be another service soon. Upon arrival, the church is empty, save for Fredrik, the organist, and Algot, the church’s caretaker. With rather unfortunate timing, Algot decides to have a casual conversation with Tomas about theology, which is less of a conversation, and more of Algot monologue-ing in Tomas’s presence. He wonders: why do we focus so morbidly on the physical pain and suffering Jesus endured, when that physical pain was far briefer than His psychological torment? Jesus was denied and betrayed by his disciples, the men he trusted most. His followers often misunderstood his teachings, which must have been enormously frustrating, and they had a tendency to disobey his commands. Worst of all, as he cried out to God while on the cross, he received no answer. Algot asks,

“Wasn’t God’s silence worse?”

Tomas utters but one word:

“Yes.”

As Algot wonders about the nature of the Passion, the organist Fredrik attempts to convince Marta to leave this place. Tomas will never love her the way she wants to be loved. The town, and even its own pastor, have lost their faith. Their small community is devastated by the threat of nuclear apocalypse. According to Fredrik, she has no place left there. She responds to this in a way that contradicts her character: she prays.

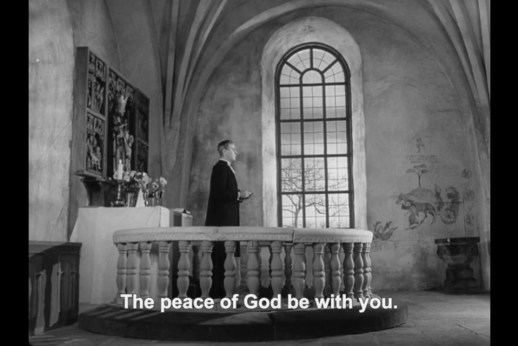

No one has shown up to this afternoon’s service. Algot and Fredrick consider the possibility of cancelling the service, as there’s no point in holding one without a congregation. Tomas disagrees, and kneels down to pray briefly. He rises, the church bells are rung, and from behind the pulpit, he declares:

“Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of Hosts. The whole earth is full of His glory.”

Winter Light’s ending is somewhat ambiguous. I see at least two major interpretations here. In the first, Tomas becomes aware of his own doubts about his faith at the beginning of the film, as prompted by his initial conversation with Jonas. After his encounter with Marta, he finally loses the last shred of that faith, and he declares his freedom from belief. Once he reveals the truth of his fall from grace to Jonas, Jonas kills himself, forcing Tomas to re-evaluate not his lack of faith, but the impact that lack of faith may have on others. By the end, he makes the decision to continue going through the motions of being a pastor for the sake of others, ignoring his existential dilemma just as he did during the war. This is a tragic interpretation, as Tomas is essentially an ideological martyr, forever in the servitude of humanity, in all its cruelty.

Alternately, there’s evidence to support that Tomas’s trajectory of doubt has come full circle by the end. Through questioning and pondering the nature of God, he has finally accepted that he may never understand His silence, or perhaps feels that he now fully understands. Regardless, he finds stability in his uncertainty, and is now able to perform his duties as a pastor.

I’ve always admired the ambiguity afforded to us by Bergman. Depending on the way you choose to interpret this story, those final seconds of Tomas boldly returning to his station as a pastor are either chillingly devastating and tragic, or uplifting and hopeful. Neither of these feels like the objective path Bergman was taking, and if that’s the case, this is some damn fine film-making.

Speaking of craftsmanship, Winter Light, as most Bergman films, had the benefit of having Sven Nykvist in charge of cinematography. The two collaborated on most of Bergman’s more well-known films, and it’s Nykvist that’s really responsible for what we now know as the look and feel of Bergman. Every shot is very deliberately framed; the lighting is as free of shadows as possible so as to feel sterile and unnatural, reflecting the bland outward façade of the film’s characters. It’s always amazing to watch Nykvist take deliberately ugly settings and make them look interesting and convey emotions or messages through the juxtaposition of faces.

Bergman made the very sound decision to leave the soundtrack behind. The only music in this film is that of a character who is actually playing an organ, leaving plenty of deafening silence between conversations; the silence of God. The acting, directing, and writing of Winter Light are all fantastic as well. I could fellate this movie for hours, but we aren’t even here to talk about Winter Light. This is a review of First Reformed.

Winter Light: 10/10

Moving on.

*Obviously, spoilers for First Reformed.*

As much as I love rambling on about how much I love Bergman, I didn’t choose to review these films in tandem arbitrarily. As I said before, First Reformed feels like a beat-for-beat remake of Winter Light for about an hour, and it’s the places where they deviate that I find the most fascinating.

First Reformed comes to us from Paul Schrader, who has, for a majority of his career, been accused of remaking Taxi Driver over and over. It’s true that many of his films share some common threads: a male protagonist looking out for an innocent younger female, a protagonist whose outsider ethics would make them the villain of another story, and a questionable redemption arc. First Reformed maintains these Schrader-isms, and in some ways, executes them far better than his past films.

Ethan Hawke’s character, Reverend Toller, is our Travis Bickle stand-in this time. He’s the pastor of a small church with an even smaller congregation, and his little church is essentially nothing more than a tourist attraction. It used to be a stop on the underground railroad, and Toller gives half-hearted tours of the building on a regular basis, pushing tourist-y merch such as coffee mugs and T-shirts.

Toller has a troubled past. It was never his plan to be a lonely priest in a shit-hole church. He was married once to Esther, the choir director, and had a child. He convinced his son to join the military, and very quickly, his son perished in Iraq. As with many couples grieving the loss of a child, they decided upon a divorce. Esther and Toller remain cordial, as Esther still has feelings for Toller, attempting to take care of him, much to his annoyance.

Business hasn’t been so great at Toller’s little church. When he was in the depths of despair after his divorce, the reverend Jeffers, played by Cedric the Entertainer in a real movie role, offered him this job as the pastor of a small congregation. Jeffers is the pastor of a mega-church, which provides the funding that keeps Toller’s church alive and running. Toller is clearly sick of being accountable to Jeffers, as we see him frequently refuse help for basic maintenance issues.

Toller is also very sick, and is often shown with a drink in his hand. He appears to have some form of cancer, and is a raging alcoholic. When Esther reaches out in an attempt to get him help, she is met with either dismissiveness or hostility. It’s very clear that Toller doesn’t want help. In fact, he’s actively trying to slowly kill himself.

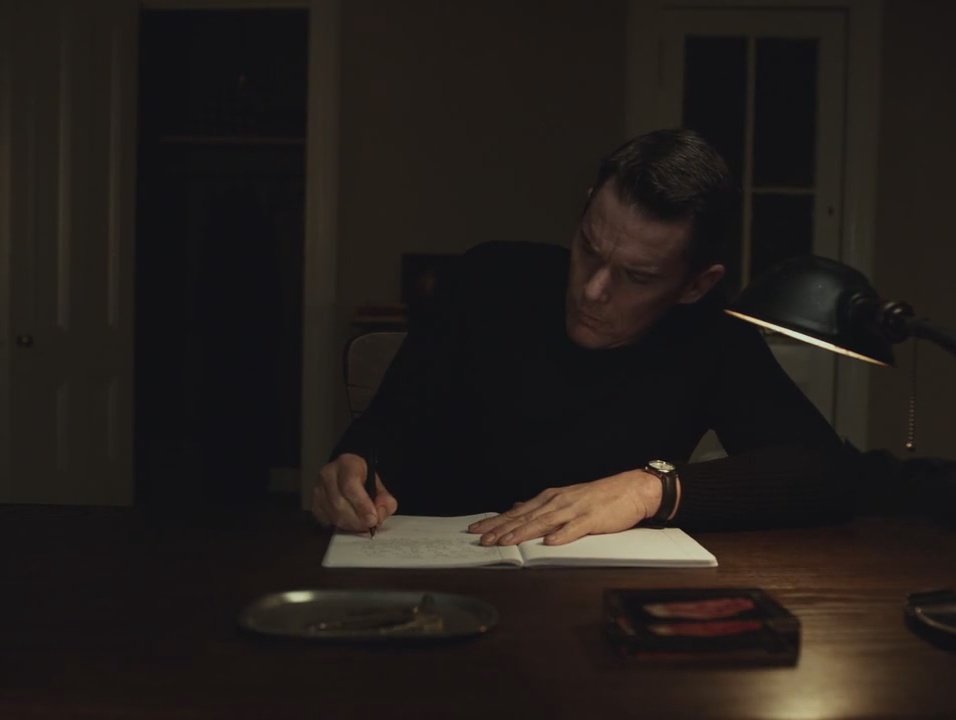

Throughout the film, we learn quite a bit of this through voice-over narration. This style can backfire, but it’s also been a strong point of Schrader’s in the past, specifically in Taxi Driver. We learn that Toller is writing this journal as a form of prayer, or self-therapy, and that in a year, the journal will be destroyed by fire. At least, this is his intention. Sometime soon, Toller and the mega-church are planning a “re-consecration” ceremony in honor of the church’s 250th anniversary.

One day, after a pathetically-attended church service, Toller is approached by the pregnant Mary (real subtle, right?), played by Amanda Seyfried. She is concerned about her husband Michael, who is a rabid environmental activist. Mary asks Toller to have a talk with Michael, and he agrees.

When Toller approaches Michael about the source of his depression, Michael goes on a long diatribe about the futility of trying to save the earth. He’s clearly suffering, as he recently lost several friends during a series of protests that turned deadly. He drones on and on about how in 20 years, the earth will be unlivable, based on these vague scientific studies that everyone else is apparently ignoring. How can he bring a child into this world knowing that one day, he’ll have to look that child in the eye and say, “My generation did this.”

His other big concern: “Will God forgive us for what we’ve done to the earth?”

As Michael talks Toller’s ear off, Toller is clearly a bit disengaged, and not entirely convinced of Michael’s “studies.” He assures Michael that whatever pain would be caused by bringing another child into this world, aborting that child would bring about even more pain. This is Toller’s blasé attempt to comfort Michael, and it doesn’t seem to have much effect. The two agree to meet the following week.

Before their next meeting, Mary calls Toller and asks him to rush over immediately. In the garage, she has found a vest with a bomb strapped to it. Michael has been spending an unusual amount of time tinkering in the garage. Toller agrees to dispose of the bomb for her, and instructs her to tell no one.

Michael calls Toller and asks to change their meeting place to a specific location in the woods. When Toller arrives, Michael has blown his own head off with a rifle. Is this starting to sound familiar?

Mary is certainly affected by her husband’s death, but not to the degree one would assume. Toller is a great comfort to her, and the two start to get close. At a certain point, Mary asks Toller to play a game with her; a game she used to play with her husband. She lies on top of him, the two fully clothed. They lock hands and make as much physical contact as possible, moving and breathing as one. Before long, they begin to levitate, and surrounding them is a hallucinatory montage of the beauty of the earth.

The time for the big consecration ceremony is drawing closer. Toller’s health problems are worsening, and we discover that he’s been mixing Drain-O (or something similar) with his lowball glasses of scotch throughout the film. He becomes increasingly sickly, and Esther attempts to intervene. He proclaims that he never loved her, that he felt ill at the sight of her.

Toller holds Michael’s funeral service as per his last will and testament. He wanted his ashes spread across an area that had been polluted by ‘generic big business company,’ and the local church choir was to sing a Neil Young protest song while doing so.

‘Generic big business company’ turns out to be a major donor to Cedric the Entertainer’s mega-church. A representative from the company expresses his disdain for the actions of Toller, proclaiming it to be a “political act.” As Toller digs further into the company’s history, he finds that they’re responsible for a very significant amount of pollution. As he questions the representative about why they would continue their shady practices, he simply tells him that it’s a complicated issue, and he shouldn’t overthink it.

Cedric is extremely angry with Toller for challenging the representative, because he in no way intends to lose his church’s funding. He explains to Toller than he needs to start “living in the real world.” Toller asks him how the church can stand by and allow the destruction of God’s creations. Cedric replies by positing that, perhaps, this is God’s plan. He destroyed the earth once with a flood, maybe he’s keen on doing it again. Or maybe none of that matters, and Toller should just keep his mouth shut.

In an effort to show some support to Toller, Mary proclaims that she is going to show up for the consecration ceremony. Toller reacts very badly to this, begging Mary to stay away from the ceremony. She reluctantly agrees.

At this point, we see Toller trying to figure out how to use that suicide vest he confiscated from Michael. His goal becomes clear. At the consecration ceremony, he’s going to blow himself up, and take those stuffy big business guys down with him.

The day arrives, and Toller is preparing for his last hurrah. Esther sings in the church while he prepares in the adjoining parsonage. He puts the suicide vest on under his robes, and heads to the sanctuary, only to find that Mary has arrived. Dismayed and panicked, Toller returns to his parsonage and rips off the vest. He then grabs some barbed wire and wraps it tightly around his entire torso until he draws a significant amount of blood, in what appears to be self-punishment. He puts his robe on over the barbed wire, with light bloodstains splotched all over.

Cedric notices that Toller is late, and goes to the parsonage to see what’s wrong, suspecting that he may be drunk. He’s unable to get inside the building, and gives up, returning to the sanctuary.

Immediately after this, Mary makes it inside the parsonage. Mary and Toller embrace, and start making out heavily. The film fades to black.

As you can see, there are plenty of key differences between First Reformed and Winter Light. Environmentalism is a stand-in for China’s nuclear development. Winter Light doesn’t involve a potential suicide bombing. Toller, in contrast with Tomas, goes perhaps a little too far when comforting the widow. Toller is actively trying to ensure his own demise. There are others, but you get the point.

Thematically, the biggest difference is that Winter Light is about characters trying desperately to understand God, his silence, and perceived cruelty. First Reformed is about understanding the church, it’s silence regarding environmentalism coupled with its Republican-dominant leanings, and the insanity and cruelty that can come from attempts to rectify this situation. It’s almost an updated Winter Light for 2018.

The acting in First Reformed is powerful. Ethan Hawke’s character is silently depressed, and refuses to allow the people in his life to witness his inevitable downfall. Because of this, we get lots of very effective brooding and verbal deflections, much like a more extreme version of Tomas. Cedric the Entertainer is actually a bright spot here as well. His rhetoric of, “just go with it, it’s how we get paid.” is rather chilling, and he absolutely nails the kind of underlying disingenuous attitude one would expect from a mega-church preacher, while still leaving enough room to keep his own personal convictions intact. It’s the sort of impressive mental gymnastics that just might earn Cedric the Entertainer a best supporting actor nomination on a slow year.

The cinematography is quite excellent, but not in the same way as Winter Light. There is no obsession with the juxtaposition of faces, but there is an affinity for clean, visually-sterile environments and symmetrical shots. First Reformed is light on score for a majority of the film, but toward the end, the score picks up, and actually becomes the film’s weak point. In a movie that handles subtlety so well for so long, it felt out of place in the final third.

The other aspect of this film that I wasn’t sure about at first was its treatment of environmentalism. As the audience, we are supposed to, by default, assume that the environmental doomsday scenario the film presents is absolutely true. At the same time, Winter Light assumed the same thing. In both, this backdrop feels like a brand of magical realism. These are cataclysmic scenarios that resemble real-world issues, but stranger, more augmented and set-in-stone versions of these scenarios.

Much like Winter Light, there are probably several ways to interpret First Reformed’s ending, but there are two that stand out to me. Upon seeing Mary in the congregation, Toller is overwhelmed with guilt, and after punishing himself, is convinced by Mary’s love that bombing the church was not a valid solution. This was my first thought, but it didn’t sit quite right with me.

There are some key details that make me believe the ending is a bit more sinister. When Cedric looks for Toller, he’s unable to find him because the door is locked. When Mary looks for him, she’s able to walk right in. Also, she expressed a degree of sympathy toward her husband’s views. This leads me to believe that, possibly, Mary and Toller had decided together to go through with the bombing, and Mary had fully intended to go down with the ship. Her showing up was a way of holding him accountable to this act, and at the end of the film, Toller goes through with it.

Regardless of what actually happens at the end, the entire film is a thrilling subversion of expectations. It’s Paul Schrader’s return to form, and while it is heavily inspired by Winter Light, Taxi Driver, every other Paul Schrader movie, and Diary of a Country Priest (which is a whole different conversation entirely), it manages to draw from all of these sources and yet still remain a very different film. I will certainly watch this film again, and it will definitely be in my top ten this year. If it weren’t for some of the heavy-handed environmentalist messages that felt rather unrealistic and the score in the third act, this would be a perfect film to me. As such:

9/10

So instead of ignoring the boring church movie, give First Reformed a try. It’s already out on certain VOD platforms, so keep an eye out.

Also, there’s a Criterion re-release of Winter Light in the works, so no more excuses about how obscure it is.