Before I dive into the history of this film, I should probably throw out a slight trigger warning. There will be talk of suicide, a subject that is completely inseparable from both the film’s plot and its notoriety. I’ll also mention that a dog is attacked and killed by another dog off-screen, and apparently animal deaths trigger people more than human deaths, so fair warning.

Also, because I really feel that knowing less is more in regard to this film, and I wish to promote it as much as possible, this will be a spoiler-free review.

He told me the other day, there is an elephant in Manzhouli. It sits there all day long. Perhaps some people keep stabbing it with forks, or maybe it just enjoys sitting there. I don’t know. People gather there, watching it sit still. They feed the elephant food, but it takes no notice. He told me that before.

The first thing you’re likely to hear about An Elephant Sitting Still involves the personal life of its writer/director, Hu Bo. At the age of 28, he published a series of short stories called “Huge Crack” or “Big Crack”, depending on the translation. The book was a huge hit in China, receiving widespread critical acclaim. Hu Bo wrote a screenplay based on one of these stories, and directed and edited the film himself. After finishing the project, and before its official release, Hu Bo committed suicide at the age of 29, allegedly because of a falling out with his producers. With this haunting scenario lingering in the back of your mind, An Elephant Sitting Still becomes a rather harrowing experience – and it’s not exactly an uplifting film to begin with, at least not on a surface level.

After finally mustering up the courage (and attention span – it’s 4 hours long) to sit through what could be interpreted as an elaborate suicide note, Hu Bo’s passing hits me even harder. Nearly every aspect of An Elephant Sitting Still impressed the hell out of me. A debut of this caliber would normally result in eager anticipation for the director’s next project, but his premature demise has made this impossible. I don’t mean to imply that my loss of potential enjoyment of his future work is even remotely as tragic as the impact his suicide has likely had on those close to him, but it’s still an awful loss for the fans he will inevitably attract.

At the same time, a story such as this could only be told as authentically as it is by someone who has lived a troubled life. Hu Bo pours every ounce of his pain, self-doubt, and frustrations about the cruelty of humanity into every frame. He crafts an uncomfortably intimate portrait of four individuals who reach their absolute breaking point, to the extent that their only motivation for continuing to exist is the anticipation that they may one day understand the urban legend hinted at in the opening of the film. It is precisely as bleak as it sounds, yet its message is not devoid of any glimmer of hope. This was the director’s final attempt at obtaining the catharsis necessary to provide the relief he so desperately cried out for. As I watched the film, my body and soul wept for Hu Bo.

Given its history and premise, An Elephant Sitting Still could have easily become a one-sided, immature love letter to the idea of nihilism as an absolute – an obnoxiously adolescent and didactic exercise in stubborn hatred for existence itself. However, Hu Bo is clearly above this. His artful articulation of the themes presented demonstrates a maturity far beyond his years. This is not the work of an individual hell-bent on forcing his own malaise upon the audience, but rather an extreme form of self-expression intended to convey a compassionate solidarity to its viewers, with the hope that they will find freedom from the existential dread that Hu Bo could not escape.

An Elephant Sitting Still would never have the tremendous impact that it does without the technical prowess it displays. The camerawork (which comes from someone named Chao Fan, another first-timer) is exceptional in both concept and execution. A majority of the film occurs in very long takes, and there are rarely static shots. The camera spends much of its time following directly behind one of the four characters (the “follow shot”), occasionally putting their face into frame when necessary. It’s a technique used frequently in the high school hallways of Gus Van Sant’s Elephant, the corridors of the Overlook Hotel in The Shining, and more recently, the entirety of Darren Aronofsky’s Mother!. The purpose of this is generally to place the audience in the character’s shoes – to make them feel as if they’re experiencing what the character is experiencing in real time. Chao Fan takes the intended intimacy of this style to a new level by keeping the camera uncomfortably close to its subject. Whereas the typical follow shot would keep most of the subject in frame unless the perspective is over-the-shoulder, Chao Fan often composes these while framing the top half of a character’s head, an unexposed arm, a kneecap, or even a thigh. It makes for a remarkably (and necessarily) claustrophobic experience.

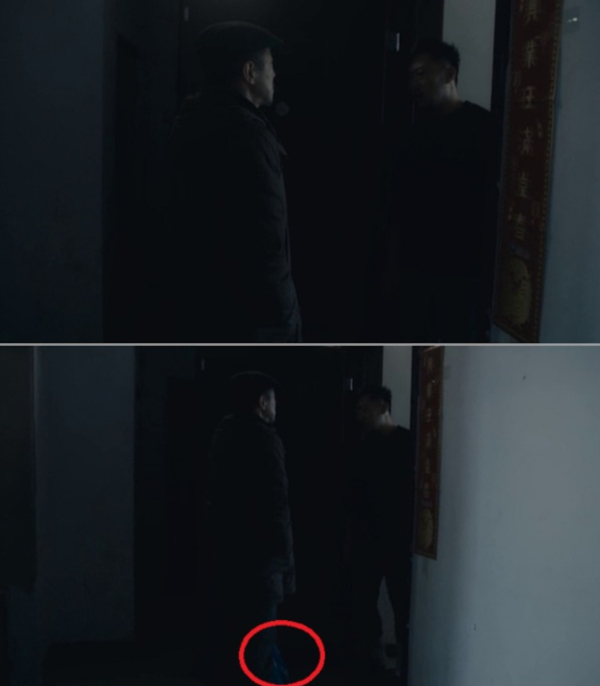

There’s also much to be said of Fan’s use of light and shadow. Many shots are intentionally so dark that the audience is not supposed to be able to clearly see the action of a particular scene, forcing the storytelling to rely on the film’s subtle sound design. The setting is dreary and full of gray concrete and dilapidated walls with aging white paint. The camera typically ensures that each of its main characters are in focus, but nearly every side character (and they abound in this story) is blurred as they interact with our protagonists. Because of the depressed, languid nature of the four main characters in this story, outbursts of emotion are usually relegated to these side characters, and their actions frequently occur either off-screen or in an unfocused background, with the camera sharply highlighting the reactions of the leads.

This combination of techniques becomes an unconventional method of storytelling. For example, it is set up at a certain point that a family has recently lost a large and aggressive white dog that is now roaming the streets. An aging man named Wang Jin, whose only sympathetic companion is a small Pomeranian, is walking down an alley and stops for a moment. The camera only shows us Wang’s face from the shoulders up with just a little bit of the alley in the background. We only infer that Wang has his dog with him from a few subtle sounds, and the fact that he occasionally glances downward and tugs on his leash. We hear the larger dog approach and maul the smaller dog off-screen as Wang kicks at the attacker. Once the larger dog (which is not seen in this shot) has run away, the camera pans out just enough to show us that the Pomeranian is panting upright on the ground, with just a little blood on its fur. The severity of the attack is unclear, and we cut to another scene.

Later on, Wang is seen (again from the shoulders up, then from the waist up) confronting the couple that owns the larger dog. He informs them of the attack rather non-specifically, and the couple look down at the off-screen canine on several occasions. Wang makes movements with his arms that are very similar to the previous scene, implying that his dog is probably at his feet, tugging on his leash. As the couple deny culpability for the attack, the camera eventually zooms out just enough to show the viewer that what Wang is holding is not a leash, but a bag he’s been fiddling with – a bag that obviously contains the body of his now-deceased beloved pet.

This is the film’s disorienting pattern. We are constantly shown reactions from our main characters as the most traumatic incidents are blurred, partially obscured, or pushed to the very edges of the screen, and it isn’t until later that we become privy to the details of the events that took place, whether through subtle camera placement or dialog. As such, An Elephant Sitting Still demands the utmost attention from its viewers, and places an unusual degree of confidence in the audience’s ability to retroactively piece events together. This is so far removed from the unfortunately prevalent practice of throwing exposition at the audience multiple times until they fully comprehend what’s going on with little to no effort that it’s both unusual and exciting to see a film with this much respect for its viewer’s intellect.

When a film goes this all-out with claustrophobic camerawork, there’s usually greater pressure on the actors to perform adequately. If there’s a camera six inches from your face and the only part that’s in frame is your forehead, your forehead better damn well have something interesting to say. Thankfully, the leads (and most side characters) live up to this expectation. It may not seem difficult to act in a film where every character is numb and almost expressionless, but in order to tell such a visual story, every muscle in your body must be prepared to convey a paragraph’s worth of emotions over the course of a few seconds. This is executed quite well, and when our somber leads do enter a highly emotional state, the impact is amplified by contrast.

By far the biggest barrier to watching An Elephant Sitting Still (aside from the need for subtitles) is its daunting run-time. It’s four hours long, and while I was consistently engaged with the story once it gained just a little momentum, the unconventional techniques at play make the first 30 minutes to an hour incredibly confusing. I foresee most viewers giving up rather quickly, which is a shame, but also understandable. This is the primary reason I feel so strongly about really selling this movie on its artistic merits. Little of what I’ve said is hyperbole, but as I’ve pointed out, this is a film that expects you to buckle down and pay attention. It won’t hold your hand when you start browsing your phone for 10 seconds during a seemingly-inconsequential scene that seems to be going on longer than it needs to, and then 30 minutes later those 10 seconds become crucial to understanding what’s going on, leaving you completely lost.

There’s a strong chance that this will be the highlight of 2019 for me, even if Once Upon A Time In Hollywood lives up to the tremendous hype, which at this point seems impossible.

Uncharacteristically, I’m going to refrain entirely from synopsizing or analyzing the plot and major themes of this one. I can only hope you’ll take my recommendation and experience An Elephant Sitting Still for yourself, drawing your own conclusions, and falling in love with the tragic brilliance of a young man named Hu Bo.

10/10

In a few days, I will turn 29 years old. Were it not for a supportive network of family and friends whom I love dearly, the right mix of medications, and auteurs such as Hu Bo who have brought into my life a broad range of perspectives, challenging stories, and emotionally-poignant entertainment…

I fear that I would be in Hu Bo’s position right now, but with a far less powerful legacy. So thank you all, from the very bottom of my heart. And thank you, Hu Bo. I know the pain was too much to bear, but you left behind a glimmer of hope for the rest of us.