God’s Not Dead 3: A Light In Darkness acts as a half-hearted apology to those who felt the first two films were offensive. In the spirit of forgiveness, I’ll be as civil as possible in this review. I make no promises.

*Spoilers for the entire God’s Not Dead franchise.*

Remember this guy? David A. R. White, founder of Pureflix, creator of horrible movies? He’s back!

Isn’t that a great head-shot? I think it’s a lovely head-shot. Soak up that positivity while you can; that may be the last positive thing I’ll ever say about this man.

For those of you who’ve had the displeasure of mentioning the God’s Not Dead franchise in my presence, it should come as no surprise that I’ve chosen to talk about the third entry. The sheer vitriol this franchise invokes in me can often result in a sudden shift in conversation, from casual chit-chat to an angry one-sided rant about socially-irresponsible Christian films. It’s not something I’m particularly proud of, but when a film’s implied message is that without David A. R. White’s particular brand of Christianity, one must be a remarkably hateful individual who secretly wants Jesus in their life, I’m going to react badly.

The first God’s Not Dead was something of a fluke. Christian cinema has been producing bad to mediocre films for decades, and traditionally, they played to a Christian audience. In the 80s and 90s, the Christiano Brothers released films like The Pretender, a movie about a high school student who pretends to be a Christian to impress a girl. That film’s message is fairly standard: pretending to be a Christian is not a nice thing to do. It’s a bit more heavy-handed than that, but this is a low-budget project that’s being screened in churches, not mainstream theaters. It knows its audience, and it plays directly to them.

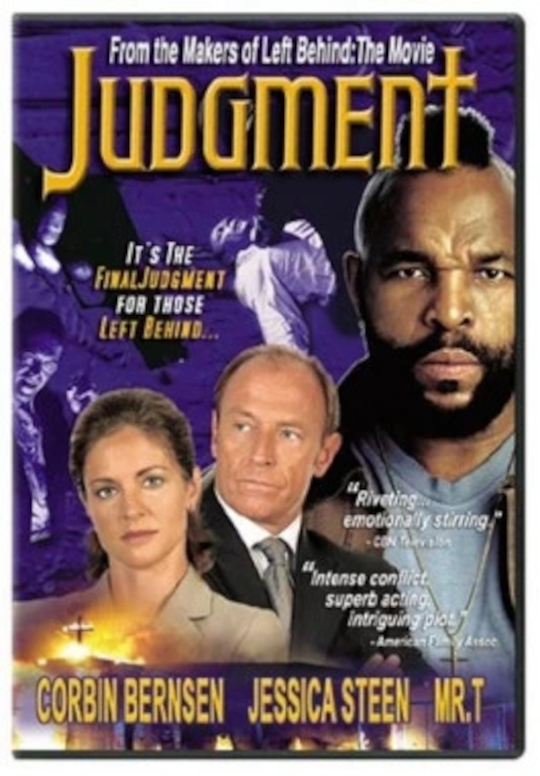

At the same time, the 1990s and early 2000s saw an influx of apocalypse-themed Christian films. They often wrangled big names like Michael York, Mr. T, Gary Busey, and the former face of the Christian film industry Kirk Cameron. Most of these involved “the rapture”, and ended with an altar call for all those non-Christian viewers out there to get right with God before he forcefully abducts His followers and leaves you stranded in an apocalyptic wasteland. Many of these were action films, or at least attempted to be, and their goal was less about garnering a Christian audience, and more about giving mainstream audiences the mindless action they crave and then doing a serious bait-and-switch, all in the name of evangelism.

The first God’s Not Dead lies somewhere in between these two approaches, at least in intent. It very much reflected a paranoid fundamentalist view, and perpetuated the idea that Christianity is constantly under attack by nasty atheists who want to take God out of our country and ruin the lives of believers. In that way, it was certainly pandering to its audience the way a film like The Pretender would, but with a more negative message. It served to affirm a worldview that encourages the notion that everyone is out to take away the freedoms of American Christians. I’m not denying that there are angry anti-theistic individuals who wish harm to the Jesus-lovers, but it’s not anywhere close to a majority of the non-Christian demographic.

Still, God’s Not Dead did more than preach to the choir. It had a moderately higher budget than most films of its kind, and painted itself as a competent drama that would “prove to you” that God isn’t dead. This wasn’t just a movie for Christians. It wanted you to know just how vile and cruel the rest of the world has been to self-proclaimed Jesus Freaks, and takes jabs at professors, intellectuals, Islam, homosexuals, left-wing politicians, and closet Christians. That film starred Kevin Sorbo as a despicable philosophy professor who tries to force his students to sign a contract that declares God is dead and religion is a farce. Many philosophy classes will call for objectivity, because it’s difficult to study the subject when you have a combative view of anything that doesn’t directly line up with your own opinions. In a real classroom setting, this would be a disclaimer, but in that film’s universe, it’s a blood-signed contract with the devil, forcing you to renounce your faith. It’s clear that this incident is modeled after a philosophy professor’s cry for objectivity, and that these filmmakers interpret objectivity as a threat to their worldview. Since the film goes for an extremist approach, we get an amplified example of this scenario, and the implications are highly anti-intellectual.

The first film also had a massive amount of sub-plots that rather lazily converge. It’s akin to Magnolia or Short Cuts, in that there isn’t necessarily one main plot thread, and by the end of the film, each storyline intersects somehow. In God’s Not Dead, that convergence point is a Newsboys concert with an inspiring message from a Duck Dynasty cast member and a tragic car accident in which David A. R. White prompts the evil professor to repent of his sins just before death, while uttering really tasteless phrases like, “In a few minutes, you’re going to know more about God than I do!” Real smooth. This is followed up by White’s magic negro friend saying, “What happened here tonight is a cause for celebration.” I get it, there’s another soul in heaven, but you’re at the site of a fatal car crash with 100+ gawkers all around. Have a little respect.

And of course, the glorious Newsboys concert includes a shout-out to the student who fought the evil professor, and a call to arms for Christians to text everyone in their contact list, “God’s not dead.” If you received an unsolicited text message with these words sometime in 2014, that’s why.

God’s Not Dead received a pretty hefty amount of criticism from both sides of the fence. Many Christians didn’t agree with the hateful treatment of its characters, and no matter what your beliefs are, it’s still a poorly-made film. However, this didn’t stop the film’s primary target audience from seeing the film in droves. Some churches even bussed whole congregations to movie theaters. On a $2 million budget, God’s Not Dead made $64.7 million back.

That’s a pretty massive return on investment, and a large chunk of that money was poured back into David A. R. White’s production company, Pureflix. Thanks to that financial kick-start, Pureflix is now churning out films at a rapid rate, and has its own streaming service. A sequel to God’s Not Dead was inevitable.

(As a side note, Michael Landon Jr., son of the great Charles Ingalls Wilder, sued Pureflix for ripping off his story. The lawsuit was dismissed, but when you consider that God’s Not Dead feels like a cynical Christian exploitation film, it really makes one wonder, doesn’t it?)

In 2016, Pureflix released a sequel, simply titled God’s Not Dead 2. There are fewer side-plots, so it’s a more focused film, but it’s still pretty awful. The premise is rather flimsy. Melissa Joan Hart is a school teacher who simply answers one student’s question about Jesus, and in the process admits that she’s a Christian. There’s nothing too heavy-handed about the way she handles this situation, and it feels fairly appropriate.

Some disgruntled parents complain, and suddenly poor Melissa Joan Hart reprises her role as Sabrina the Teenage Witch, if she were older and the setting was transplanted to Salem, MA. The ACLU sends over Ray Wise (Leland Palmer from Twin Peaks, a man who has made his career playing Satan or Satan-like characters) to handle the prosecution. His performance is just over-the-top enough to accept God’s Not Dead 2 as a so-bad-it’s-good kind of movie, but it’s a bit scary to think that these filmmakers see the ACLU as a boogeyman. It’s also starkly ironic, because this is the sort of case the ACLU has often defended, not prosecuted.

During the closing credits, we see a number of court cases referenced that are clearly meant to be examples of similar real-life scenarios. For example:

State of Washington v. Arlene’s Flowers: A same-sex couple sues a florist for refusing to provide flowers for their wedding, because the florist was an asshole.

Dobson v. Burwell: James Dobson, evangelical bigwig, sues the federal government for “forcing” them to provide “The morning after pill” in their health care plans.

Foothill Church v. California Department of Managed Health Care: A bunch of churches sued California for requiring them to pay for elective abortions as part of their health care plans.

Ghiotto v. City of San Diego: Firefighters sue for being “forced” to attend a pride parade.

Ave Maria School of Law v. Burwell: A Catholic school is “forced” to provide contraception and, of course, “The morning after pill.”

Going through the full list, you’ll find that each of these cases involves Christians refusing to have anything to do with abortion or gay marriage, even if it’s something as mundane as selling them flowers. In my opinion, some of these cases are valid, and some are really flimsy “I want to discriminate” cases that are more about making a statement against abortion or gay marriage than a valid lawsuit. Regardless of your opinion on these cases, they still have absolutely nothing to do with the case at the heart of the film. Therefore, this inclusion in the end credits is nothing more than fear-mongering. Its audience is generally not going to bother looking up these cases, and they fly by with the credits at a pretty rapid pace with little explanation, so as to bombard the audience with a plethora of examples regarding Christian “persecution.” It’s a really manipulative tactic, and it has nothing to do with Melissa Joan Hart’s scenario.

God’s Not Dead 2 was made for $5 million, a significant increase from the first film, and it made back $24.5 million. That’s not as large a profit margin as the first film, but it didn’t need to be. When you’re making low-budget films that perpetuate and affirm fear in a built-in audience, you’re pretty much guaranteed a certain degree of financial success. This has been Pureflix’s post-God’s Not Dead strategy for a while now, and it paints a not-so-flattering picture of a cash-grab mentality.

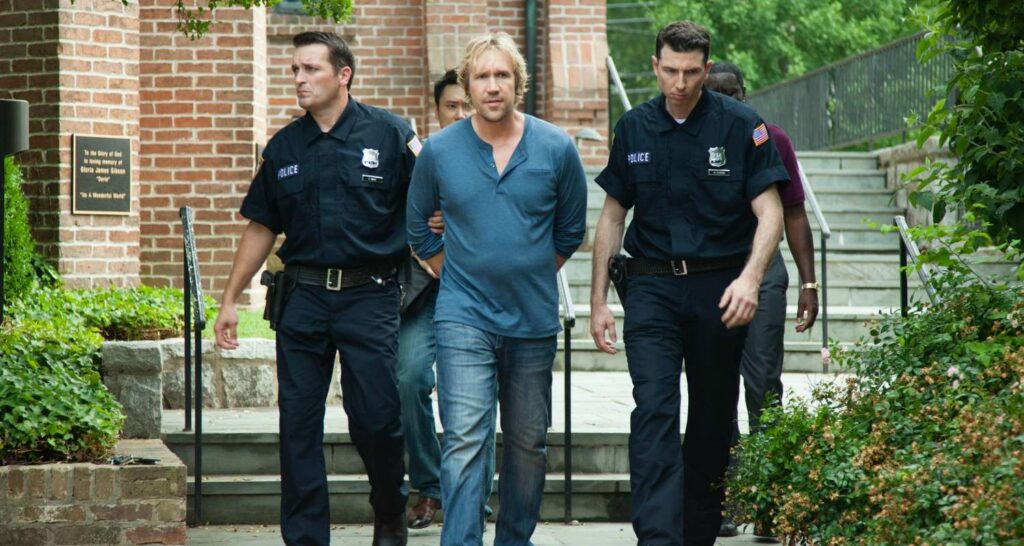

In an unexpected twist, God’s Not Dead 2 has a post-credits sequence. Earlier in the film, there’s talk of the federal government requiring pastors to submit all of their sermons. To me, this is such an unrealistic, paranoia-fueled scenario that it’s almost Orwellian. David A. R. White is arrested for neglecting (and refusing) to submit his sermons, and we have the setup for God’s Not Dead 3…

…except that this plot point is completely abandoned before the opening credits are over.

As expected, the film opens with David A. R. White in jail. It’s revealed that after a very brief stay at the county jail, he’s released due to the unconstitutional nature of this new law that may or may not have even been passed in the first place. It’s confusing. The plot never revisits this scenario, and it only serves to set up a landscape in which Christians are under attack.

We discover that the church Jesus A. R. White has operated throughout the series is actually located directly on the college campus of the first film. The school board suddenly views this as a problem after White’s little sermon scandal, and wants his church gone. For whatever reason, this also leads several college students to protest the church, nearly all of whom are extremely angry. Good luck getting college students in real life to care about anything that much, let alone the campus church. White’s church has to hire security guards to protect them from the angry hoard of ten to twenty students, which is portrayed as “just another thing churches have to do these days.”

At the same time, Keaton is struggling with her faith. Her boyfriend is an atheist, and she’s never really been too hardcore about the Jesus thing. He keeps pressuring her to give up her Jesus fantasy and move on. The couple is hanging out with their extraordinarily pretentious friends one day, and somehow they get on the topic of the Mandela effect.

The Mandela effect has been a thorn in the internet’s flesh for a while now. Simply put, it’s a scenario where a vast amount of people remember something from the past incorrectly in the same way. For example, it was a popularly-held belief that Nelson Mandela had died in the 80s, even though he was still alive. The primary example of this used in the film involves whether or not Kit Kat was hyphenated. What irks me so much about this concept is that instead of coming to the conclusion that this is just a really interesting phenomena, it’s attributed to evidence of alternate universes. These pretentious college kids don’t hesitate to jump straight to that scenario, and then immediately apply this logic to the existence of Jesus. What?

Keaton half-heartedly defends her faith to her peers, and then storms off, her boyfriend Adam just behind. Adam gives her that “I thought we talked about this” face, and she breaks up with him. Heartbroken, Adam gets wasted. On his way home from a party, he sees the campus church. The sign in front says “All are welcome,” to which Adam audibly replies, “Yeah right!” He suddenly feels compelled (probably by Satan!) to graffiti a red X on the sign and throw a brick through the basement window.

After Adam’s vandalistic shenanigans, David A. R. White and his Magic Negro, Jude, arrive at the scene of the crime, just missing Adam as he runs away. Jude runs into the church basement, because this brick has apparently knocked something over that caused the basement to ignite. White runs in after him, only to discover that his precious Jude is on fire. As he tries to pull him out of the inferno, Jude dies a really questionable and pathetic death, while White says, “Dude. Dude? Dude!” Oscar-worthy acting for sure.

“What happened here tonight is a cause for celebration,” right David A. R. White?

This incident is of course treated as a hate crime, and the school board has finally had it. Apparently the mere presence of this church on campus has drastically lowered their attendance, and so they recruit the school board member who is closest to White to deliver the bad news. During conversations with this school board, each member behaves like a complete sociopath. They essentially pick White’s closest friend to break the news out of sheer spite, and as a test of loyalty.

During Jude’s funeral, White encounters Jude’s parents. He comes to them for advice, and he gets some sagely wisdom from Jude’s mother. This is going to become a pattern. When White needs advice, he seeks out the nearest African-American and unloads his problems. White grieves for Jude for about three seconds, having a complete breakdown while jogging.

Being understandably upset about the school board selling the church behind White’s back (way more upset than he was about Jude’s death), he recruits the help of his estranged brother Pearce, played by John Corbett, who happens to be a lawyer. We see plenty of sibling rivalry scenarios, many of which end in White pouting like a child. In fact, they both act like children, and these scenes are somewhere between intended comic relief and deadly serious. It’s difficult to tell the difference. White gets angry with Pearce about his worldly ways, condemning his drinking and philandering. Pearce constantly mocks White for his faith, and invades his house during the inevitable court case, throwing darts at the wall and just being generally disrespectful.

Now that White’s church doesn’t legally belong to him or the school, the new owners decide to knock down the church in order to build a student union. This begs the question: who bought the church? Because it sounds an awful lot like the school still owns the building. When White sees some bulldozers ready to knock his building over, he stands in front of them as the disgruntled construction workers (who, in spite of just doing their job, absolutely hate White and his church) warn him to leave. Instead, White gathers some protesters and congregation members around and begins the most boring and effective of filibusters: reading aloud the Bible from cover to cover. Eventually, Pearce returns with a temporary reprieve from the demolition, and the church is saved for now. The police and construction workers are very, very disappointed.

The dynamic between White and his brother Pearce goes some rather strange places from here on out. As White cries and moans about his plight, Pearce delivers a wonderfully self-aware line: “You guys just love to play the victim card, don’t you?”

For a moment it appears that God’s Not Dead 3 has become aware of its own martyr complex, at least until White derails any impact this line could’ve had by saying, “You guys?”

Get it? Because white Christians are a minority, just like African-Americans? Yes, White is complaining about being generalized.

This turns into a really, really typical argument about the nature of religion. Pearce talks about how man has committed atrocities in the name of Jesus for centuries, and persecutes people while playing the victim at the same time. White’s counter-argument is that these are just a few freak occurrences, and that there are far more examples of religion doing good. It’s a pretty played-out argument, and just like when this argument plays out in real life, they never reach a conclusion.

Amidst this mess of a plot, we find out that White has a love interest, who he gets really defensive about like a child. In the middle of the film, they go on a pseudo-date, and see some guy using a pottery wheel. I thought to myself, “surely this isn’t going to be a metaphor about God being a potter, shaping and molding our lives…” and I was wrong. By the end, the love interest relays this metaphor, ensuring that God’s Not Dead 3 fully intends to amp the cliché factor up to 11. This is the only function she serves.

As this is going on, Adam and Keaton are still wrestling with whether or not to continue hiding the truth about the brick incident. As Adam sulks at a party, Keaton makes the mistake of asking him, “What’s wrong?” We then get Adam’s how-I-became-an-atheist story. His father was extremely abusive, and so his mother filed for divorce. Instead of supporting her, their church humiliated her, calling her a sinner, and telling her that she would be an adulteress if she married again. Now that this is out in the open, Keaton can tell him that everything is okay, and Adam can find the courage to confess.

White receives an anonymous text that identifies Adam as the person who threw a brick through the church window. This text is sent by Adam himself. After White publicly assaults him, he eventually learns to forgive him for reasons the movie doesn’t care to go into. Jesus, I guess?

At the end of his rope, White pays a visit to a black pastor friend…to seek his sagely advice. This scene provides us with a brief glimmer of hope that perhaps this movie “gets it” after all. After listening to White bitch about how it’s time Christians stand up for themselves, the black pastor replies angrily.

“I’m a black pastor in the south. People throw bricks through my church window DAILY!”

This guy has a really good point. Here’s David A. R. White complaining about being persecuted to a Christian who has endured real persecution on a persistent basis, and doesn’t complain about it at all. Seeing White finally get called out is great, but he’s mostly unphased by this remark. The movie moves on, and the pastor delivers his sagely advice.

As the court case begins to heat up, so does the tension between White and Pearce. Pearce finally reveals why he holds so much resentment against White. Pearce began simply asking questions about the existence of God in his late teens. Their parents reacted quite badly to this, and he was essentially forced to leave home, losing the favor of his parents. When their health began to fail, it was White who took care of them until the end, because Pearce wasn’t exactly welcome to come home due to his “wild” lifestyle.

David goes on “The News”, to tell everyone to email-bomb the school board about the church issue. His interview “goes viral”, because that’s what region-specific local news does, and there’s a decent turnout of support.

After all of this BS, David A. R. White has a change of heart. Kind of. He stands before a crowd of protesters and supporters in front of his church, and delivers a heartfelt message. He’s going to drop the lawsuit, and when the new student union center is built in the church’s place, he will appoint Josh Wheaton (the student who goes to war with the evil professor in the first movie) to be the pastor of a group that will meet inside the student union.

….Huh?

This option was never once presented to anyone, and if it had been, White’s defense during this entire film could be boiled down to “but it’s a historic building.” Does White even have the authority to make this declaration? There is no conversation about this, and we are forced to accept that White has once again saved the day, this time by finding a compromise. I think this is supposed to be some kind of a unifying moment, because all of a sudden both protesters and supporters are holding candles.

Keaton eerily re-reads the text message she sent so long ago that says, “God’s Not Dead”, and the movie ends.

There are so many instances in God’s Not Dead 3 that had me wondering if perhaps David A. R. White finally took some of the criticisms of the first two films to heart, and is in some way apologizing for them. The pastoral incident is definitely one of those instances, but it’s played off really quickly. John Corbett’s character is at least humanized, but he still has a tragic backstory that lead him to be an atheist, sort of. Toward the end of the film, Keaton says, “It’s hard to see what Christians are for, but it’s easy to see what they’re against.” Ultimately, the film’s intended message is that Christians should stop being so damn judgmental, but this is subverted fairly often throughout the film, and usually in circumstances already covered in the first two films.

There is one major character that I’ve yet to speak much on who really confused me, because he’s so pious, smug, and droll that he just oozes judgment. This is the character of Josh Wheaton from the first movie. I believe he had a very small role in God’s Not Dead 2, but as the primary protagonist of the first movie, his character has changed completely.

Josh was once the timid victim, learning to stand up for his faith. His timidity was actually frustrating, but that’s all gone in God’s Not Dead 3. His character dropped out of college to pursue evangelism full-time, and he demands a certain degree of respect for this now. His voice is almost completely different. It’s deeper and quieter, but almost menacing, a little like Christian Bale’s Batman. Characters are constantly going to him for advice, and he just quotes Bible verses to them in the most condescending way possible. He interprets these verses for the characters, then tells them why they’re fuck-ups. In the end, his character is rewarded with his own church. It’s like a bizarre subplot that happens behind the scenes, and it’s tonally different from the rest of the film.

Another big factor into my conclusion that these filmmakers have not learned their lesson involves the movie’s use of news anchors. These are generic anchors on a generic local news program, and they tell us what to think every step of the way. Every 15-20 minutes, we get a series of conversations about the incidents that are happening in the film, and the various arguments that could be made about each issue. It’s the most intellectually disrespectful statement a film can make, and in a series rife with intellectual disrespect, that’s almost impressive.

This is a strange statement to make, but God’s Not Dead 3 is the best in the series. It’s still socially irresponsible, it still involves perpetuation of the Christian martyr complex, and the plot just sort of ends itself by telling us that none of the previous events really mattered, because the characters should have been more concerned with not being assholes to each other. Still, it takes the time to ask the right questions at certain points, and while the conclusions it draws are either tangentially related or just plain silly, they’re not as grossly offensive as the rest of the franchise. There’s less demonization, and other than the school board, there are fewer atheist boogeymen.

God’s Not Dead 3 is something of an apology, without actually apologizing. It is that emotionally distant father who stops being a dick to you, but doesn’t ever outright express how sorry he is, because that wouldn’t be manly.

Just like the son who realizes that this toxic masculinity is complete bullshit and deserves a legitimate verbal apology, Christians are evidently getting wise to David A. R. White’s tricks as well. The film’s budget is an enigma to me, but my guess is it was likely around the same as the other two, perhaps somewhere between $5 million and $7 million. Those numbers are purely speculative. The film earned $6.5 million worldwide. I don’t know how that compares to its actual budget, but it can’t be good, and it certainly continues the trend of diminishing returns in the franchise. Perhaps Christian audiences are tired of crappy entertainment that exploits their religious beliefs, and exists solely to reach deep into their pockets and rob them of their hard-earned cash.

Let us hope this film marks the end of the franchise. Goodbye David A. R. White. I’ll either see you in hell, or in the next Pureflix film. I don’t know which I look forward to less.

3/10