It’s been a really, really long time since I’ve posted a review to this site. During the slow comedown of the pandemic, it’s been difficult to find time to write, or even watch films in the first place. I have a new job, I now exercise compulsively, and my life is generally “different” in many positive ways. Unfortunately, this means publishing to this site is lower on my list of priorities at the moment. While it may feel like it, this site isn’t dead yet. I’m back, and while I can’t publish as often as I’d like, I’m not giving up.

Over the years, adapting Frank Herbert’s 1965 novel Dune to the big screen has become a sick joke. Many fans have clamored for a proper film version since its publication, but for every optimistic Dune loyalist, there’s a dejected fanboy who just wishes Hollywood would stop trying to ruin their favorite franchise in new and interesting ways.

Nearly every “visionary” director has cited Dune as their dream project at one point or another. This is so prevalent that it now amounts to a cliché, and the mark of a truly naïve faux-auteur. When you adapt Dune, you’re going to fuck it up in one way or another. A faithful or even mostly-comprehensive adaptation would likely bore audiences to tears, and a loose adaptation could invite death threats and both literal and non-literal flaming bags of feces positioned inconveniently at one’s doorstep. When it was announced that Denis Villeneuve (the man who saved Blade Runner) would direct this most recent attempt, with Timothée “Peach-Lover” Chalamet as the star, millions of Dune fans clenched their sphincters in anticipation and anxiety. This anal response stems from a series of failures and false starts that span nearly 50 years.

1972-1973: Arthur P. Jacobs

In 1972, producer Arthur P. Jacobs of Planet of the Apes fame was approached by two screenwriters with a treatment for a Dune adaptation. Jacobs brought David Lean on board as director, most likely after the success of Lean’s sand-porno Lawrence of Arabia. For whatever reason, the original screenwriter attached was replaced by Rospo Pallenberg, made famous by his role as “Additional Crew” in 1972’s Deliverance, and before his story treatment was completed, Jacobs’ production company announced a tentative release date of the first quarter of 1974. Jacobs managed to obtain funding for the film, and then died unexpectedly of a heart attack. Not unexpectedly, the rights to adapt Dune were tied to his estate, and production halted.

1974-1976: Alejandro Jodorowsky

A French company purchased the rights to the Dune franchise in 1974, and made the grave mistake of putting the project in the hands of Alejandro Jodorowsky, a Chilean/Mexican filmmaker known at the time for his surreal and highly symbolic epics El Topo (1970) and The Holy Mountain (1973).

Jodorowsky’s attempt has since become notorious, especially after the release of the shockingly entertaining 2013 documentary Jodorowsky’s Dune, which details the director’s unorthodox approach to adapting the book. He began recruiting writers, actors, and musicians almost immediately, but saw no reason to read the source material first. His intention was to use the book as the basis for a 14-hour movie that, while not faithful in any way, still had the potential to be incredible in its own right.

Among the dream team Jodorowsky pursued were:

Orson Welles, who was overweight enough by the 1970s to play the Baron Harkonnen

H.R. Giger, who would later gain notoriety for designing the alien in Alien (1979)

Pink Floyd, who were to compose much of the soundtrack

Salvador Dali as the Padishah Emperor

David Carradine as Leto Atreides

Charlette Rampling as Lady Jessica (although she rejected the role)

Gloria Swanson, ever ready for her close-up, as the reverend mother Gaius

Mick Jagger as Feyd-Rautha

And finally, screenwriter Dan O’Bannon, who spent some significant time in a psychiatric hospital after the failure of Jodorowsky’s Dune, wrote 12 screenplays that never saw the light of day, and then penned Alien (1979) and became immortal.

This all sounds remarkable, but not to a studio that would have to drop $10-$20 million on a 14-hour epic that the average human would be unable to sit through. Frank Herbert himself decided to visit Jodorowsky’s set very early on, and to the horror of nearly everyone involved, $2 million had already been spent on pre-production alone. The director’s financial negligence led to him being taken off the project.

1976-1980: Dino De Laurentiis and Ridley Scott

With Jodorowsky’s version dead in the water, his production company was more than happy to sell the rights to prolific Italian producer Dino De Laurentiis, and a major part of that deal involved commissioning Frank Herbert to write the screenplay himself, rather than serve solely as a technical advisor. By 1978, Herbert had completed his 175-page screenplay, which was nearly unfilmable.

De Laurentiis made a new deal in 1979, and brought Ridley Scott on board after the success of Alien. H.R. Giger was brought back for storyboards, and Herbert was still attached to write the screenplay, but with heavy supervision from Scott and a handful of other writers, including Rudolph Wurlitzer. Wurlitzer completed a first draft, and Herbert threw a fit when he discovered that his script had been dumbed down for general audiences.

The final draft Wurlitzer worked on tested the boundaries of good taste. In this version, the protagonist and his mother have an incestuous relationship, and in part because his mother eventually gives birth to a major character, Scott (and likely everyone else involved) thought this was too much. Scott left the production right around this time, and while I can only assume, my guess is that his departure was an attempt to preserve his future career without being known as “the guy who directed that incest-y sci-fi movie.” The official story is that Scott left due to the death of a family member, but knowing these details, I am skeptical that this was the only reason.

By 1980, production shut down.

1981-1988: David Lynch

After the previous failed production, De Laurentiis renegotiated the rights to film Dune and all future entries in the book series (Herbert was still publishing sequels at the time.) Upon viewing David Lynch’s 1980 film The Elephant Man, Laurentiis recruited Lynch to direct. For those familiar with the rest of Lynch’s career, it should be apparent that Laurentiis was not making a very informed decision. For a very long time, The Elephant Man stood out as an anomaly in Lynch’s career as his most “normal” movie – the one without a crying fish-baby, plot-relevant otherworldly little people, or a non-linear story-line.

At the time, Lynch was attached to direct Return of the Jedi, but he eventually told Lucasfilm to suck it when the opportunity to pursue Dune arose. Lynch began composing the script with two other writers, but they parted ways over creative differences. By 1982, Lynch had a draft completed, but after principal photography began, numerous changes were made without his oversight, including heavy narration to shorten the film and make the plot easier to understand. This Dune also had a star-studded cast, somewhat in the vein of Jodorowsky’s version, that included Sting (playing the same character Mick Jagger would have played,) Max Von Sydow, Virginia Madsen, Kyle MacLachlan, Brad Dourif, Jack Nance, and Patrick Stewart, with musical contributions by Dorothy’s precious dog Toto.

In December of 1984, David Lynch’s Dune was unleashed upon the world. Structurally, because of studio interference, it was a complete mess, and it was criticized not only for deviating from the source material, but for being notably bizarre, campy, and often boring. There has been significant critical re-evaluation in recent years, and this version has a strong following, but to this day, Lynch speaks about Dune with disappointment and frustration.

A longer cut of the film was released for television. The additional footage and restructuring led to a 3-hour runtime, and while these were intended to improve the film, Lynch felt it had the opposite effect. He forced the producers to remove his name from the credits, and replaced them with pseudonyms – Alan Smithee as director, and Judas Booth as writer.

1996-2003: Those Two Mini-Series

Richard P. Rubinstein, producer of Dawn of the Dead and Pet Sematary, acquired Dune’s rights in 1996. In 2000, Rubinstein’s mini-series version of Dune, made for the Sci-Fi Channel, was released to moderate critical acclaim. It was a much more faithful adaptation, and the mini-series format allowed more of the plot to be explored. It won two Emmys, but viewing it in 2021 is a painful experience due to dated special effects and TV-level performances. In 2003, a sequel series titled Children of Dune was released, and received a similar reception. Further sequels, and potentially a TV show, were in the works. The newly re-dubbed SyFy channel dropped the ball, and Rubinstein lost the rights to adapt.

2007: The Spanish Version

For nearly a decade, a group of Spanish students filmed their own unauthorized version of Dune. A trailer appeared on YouTube, and the Herbert estate slapped it down quickly. To my knowledge, it has never seen the light of day, and we are likely better off for that.

2008: Paramount

Paramount studios decided to take a crack at an adaptation, and recruited the Taken guy and actor-turned-director Peter Berg. After four years of immense failure, Paramount gave up, and Peter Berg spent the rest of his career directing mediocre war films, often inspired by true stories, and a few were mysteriously nominated for Oscars.

2013: The Documentary

At the Cannes Film Festival, a documentary entitled Jodorowsky’s Dune was released to widespread critical acclaim. It detailed the production issues of the film, and the insanity of Jodorowsky’s vision. It also created a renewed interest in the franchise.

2016-2017: Legendary Acquisition

Legendary Entertainment Productions bought the rights to adapt Dune, and began their search for a director who wouldn’t fuck this up. Denis Villeneuve (Enemy, Blade Runner 2049, Prisoners) received significant publicity after his film Arrival was nominated for Best Picture. In interviews, he couldn’t shut up about how much he loved Dune. Legendary hired him as director, and he took his sweet time making the film.

2020: Halt

A pandemic happened. Production was delayed. Everyone on earth watched Tiger King.

2021: The New One

Villeneuve is finally able to unleash his vision of Dune upon the world, and here we are.

With such a troubled history, it’s absolutely incredible that Villeneuve’s version exists, and even more incredible that it isn’t a total disaster. However, I was still skeptical going in. Dune fans have really taken a beating over the years, and this could easily have been an awful travesty of a film. I am very happy to report that it is not. It isn’t doing too bad at the box office, the critical response has been positive, and we finally have the closest thing we’re going to get to a real Dune movie. Almost…

To make any further commentary, I’m afraid I have to veer into spoiler territory. This is based on a book that’s over 50 years old, but I would still recommend avoiding spoilers even if you’re a fan. I will also include many references to characters, plot points, and locations from the book, without bothering to explain them to you, so a little Dune nerd-cred going into this wouldn’t hurt. As always, continue at your own risk.

After the title card appears at the beginning of the film, there’s a block of text that begins forming below it. “Part One.” I’ll admit, the moment I saw that, my heart sank. I was looking forward to a full adaptation, not the first half of the book. On one hand, expanding the story into two films will allow for a more faithful experience. On the other hand, I have to wait another two years before I can really make my mind up about this film. That doesn’t mean I don’t have opinions.

There are several key components of the story that have been changed this time around, and I won’t know if they were for the best until I see the payoff. The most glaring of these is the absence of the character Feyd-Rautha Harkonnen. Feyd is a major antagonist in the book, and his rivalry with Paul is very important to the second half of the story. In this version, he is never seen or mentioned, and that leaves the ending of part two wide open.

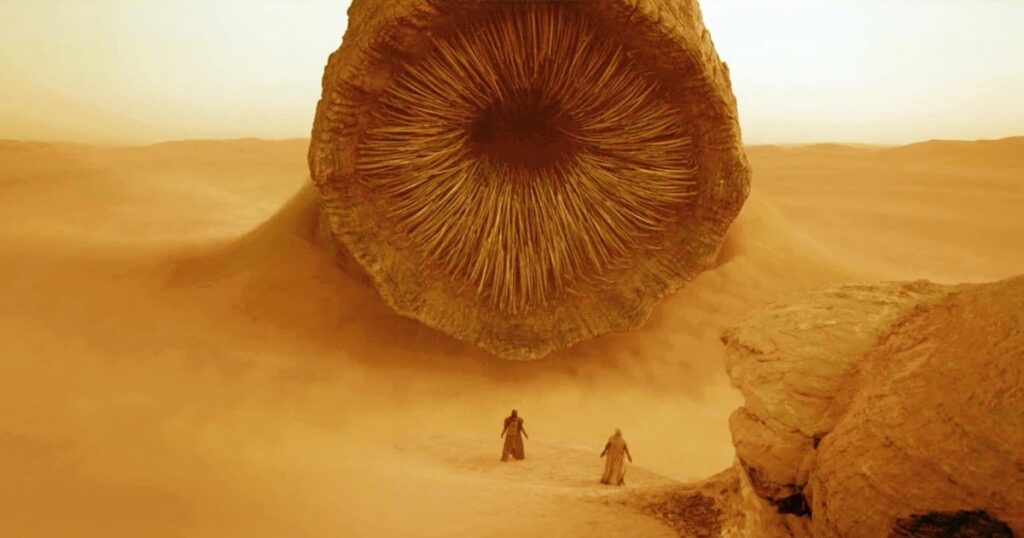

As one would hope and expect, Dune is a visually arresting experience. You can practically see dollar signs pouring out of every sandworm’s CGI mouth. The visual effects aren’t always perfect, but they’re immersive enough that imperfections don’t ever become too problematic.

Unlike other adaptations, we spend a far more significant amount of time on the desert planet of Arrakis, and while I did develop sand fatigue eventually, there was enough going on for me to ignore my own deep hatred for on-screen deserts. The costume design and visual aspects of world-building are very impressive, but they also factor into one of my biggest gripes about this new Dune universe.

Almost everything in this movie feels sparse. In other adaptations, where we spend less time on Arrakis, we are treated to many glimpses of several other key planets. Each one feels alive, and especially in the mini-series, we see plenty of crowd shots to indicate that these planets are inhabited. In this version of Dune, a majority of the film is made up of conversations between 2-3 characters at a time, and the spaces they occupy are usually empty. I assume this artistic choice was made to emphasize how isolated the Atreides family are from the rest of the galaxy, and that is certainly felt, but it also leads to a rather lifeless vibe sometimes.

As I alluded to before regarding Feyd-Rautha, some of the characters from the book have been shifted around, omitted, or absorbed into other characters. I’m very okay with that, because it was a nearly inevitable compromise. However, several of the major orders and cultures from the book are represented by only one or two characters. For example, in other adaptations, most major Bene Gesserit characters seems to travel in packs. Here, the most Bene Gesserit action we see involves the reverend mother Gaius alone in a room with Paul for five minutes. This same sequence happens in the book and every other adaptation, with Paul and Gaius alone, but here, it’s our primary Bene Gesserit experience. It should be noted that Villeneuve is apparently producing a show specifically about the Bene Gesserit order, which could explain their slightly diminished role in the film.

Speaking of the sequence with Paul and Gaius, I was not a fan of Lady Jessica’s role here. Jessica, Paul’s mother, is elevated to a secondary lead throughout the film, and for the most part I thought that decision paid off, primarily because Rebecca Ferguson is a great actress. However, the decision to allow Lady Jessica to recite the Litany of Fear as she “psychically aided” Paul was a little obnoxious, especially given the iconic nature of the Litany itself. This is also a petty Dune nerd complaint, and while I’m aware of that, I still hated this choice.

While I’m on petty Dune nerd complaints, let’s talk about The Spice Melange. In this film, we learn in an early monologue that spice is super expensive, it makes ships fly, and sometimes it turns your eyes blue. This is an egregiously simple interpretation of one of the most interesting space-drugs in all of science fictions. The properties and economics of The Spice are what drive the plot of the novel. All of these aristocrats are fighting for this particular resource because of its monetary value on the surface, but most are also driven by their out-of-control addiction to consuming spice, which has highly-addictive psychoactive effects. The blue eyes were a mark of spice addiction, but also an indication of wealth. If you’re addicted to it, it means you can probably afford it. It’s really expensive space-coke, but cooler.

When we visit Arrakis, where the locals are surrounded by spice, blue eyes are normal, and an important part of local (Fremen) culture. Basically, THE FREMEN ARE TRIPPING BALLS ALL THE TIME – yet another reason for the aristocrats of Dune’s universe to see them as an obstacle or a threat.

This adaptation explores none of that. Spice almost serves as a MacGuffin, and that’s disappointing. It also makes the Fremen feel a bit more like “noble savages” to me, but take that with a grain of sand. Still, I understand the need to trim down some of the more complex concepts in Dune, and this is but a small sacrifice to make.

It’s very, very easy to look at any Dune adaptation and criticize its faithfulness to the source material while losing sight of whether the damn film is any good. In terms of adapting Dune in a way that general audiences can digest without pissing off too many fans, this version really is a tremendous success, and I have to applaud that. Villeneuve was the right choice to direct, and I’m pleased with the final product for the most part.

Still, Villeneuve didn’t really make a film. He made half a film. As a testament to the immense size of his balls, this guy released an unfinished adaptation of one of the most volatile pieces of media ever without having obtained the funding for part two. You can feel it throughout the film. While leaving some plot threads open was bound to happen, it felt like some creative decisions and deviations from the source material may have been meant to drum up financial excitement for the second half, rather than add anything substantial.

I think the best example of this is the casting of Disney Victim Zendaya as Chani, Paul’s love interest. With a star-studded cast that have already proven themselves in other films, audiences were curious whether or not Zendaya would completely fuck this up and ruin her career, as most Disney Victims tend to do when given this kind of opportunity.

Her role in the film isn’t very substantial. She does a little voice-over, she appears in a recurring dream of Paul’s where she looks at the camera in slo-mo and begs the audience for money, and makes a cameo at the end to set up the next movie. That’s it. I know this character isn’t hugely present in the first half of the book, but frankly, it felt like a cheap casting choice. Still, it’s so hard to tell because THIS MOVIE ISN’T FINISHED. My problem is that Zendaya keeps gazing at me with those fund-me eyes, and it isn’t working for me. It’s as if Villeneuve is pitching us a pilot in hopes that Dune becomes a successful franchise, and if it works, great, but it still feels a little cynical to me.

My gripes with Dune, while stated strongly, weren’t enough to ruin the entire film for me. I’m excited to see where this goes, I just feel that I have to withhold judgment until I see the full picture.

Thankfully, it took about a week after its release for the announcement that Dune: Part Two had been green-lit. This won’t be our last chance to experience this universe, and overall, I approve.

For now: