2019 has been an interesting year for foreign cinema. For the first time ever, I feel the film industry slowly crawling away from the Americentrism it’s traditionally been known for – not counting China’s massive financial stranglehold on the market. The Chinese seem to love American blockbusters (at least that’s what the box office numbers tell us), but this year has shown us that it’s not just what’s going in to foreign film markets that we need to pay attention to, but what’s coming out of them as well. That’s not to say other parts of the world have traditionally been devoid of artful cinema, but rather that foreign cinema has always felt somewhat low-profile in America. This is still a problem in terms of theatrical distribution, but a disproportionate number of the best-reviewed films this year are foreign.

Already, we have:

The Farewell, Climax, Ash is Purest White, Shadow, Leto, An Elephant Sitting Still, Photograph, The Wild Pear Tree, Tigers Are Not Afraid, Birds of Passage, The Heiresses, Woman at War, Too Late to Die Young, 3 Faces, Everybody Knows, Cold Case Hammarskjöld, Knife + Heart, Sorry Angel, Dogman, Luz, Diamantino, The Image Book, Non-Fiction, Sauvage/Wild, Rafiki, Long Day’s Journey Into Night, The Chambermaid…

…and others that I’m sure I’m forgetting. That’s a pretty daunting list for a year that isn’t over yet, and it makes me wonder if I should even bother with American films at this point. We also have another film to add to this list, and I must say I take great pleasure in this addition:

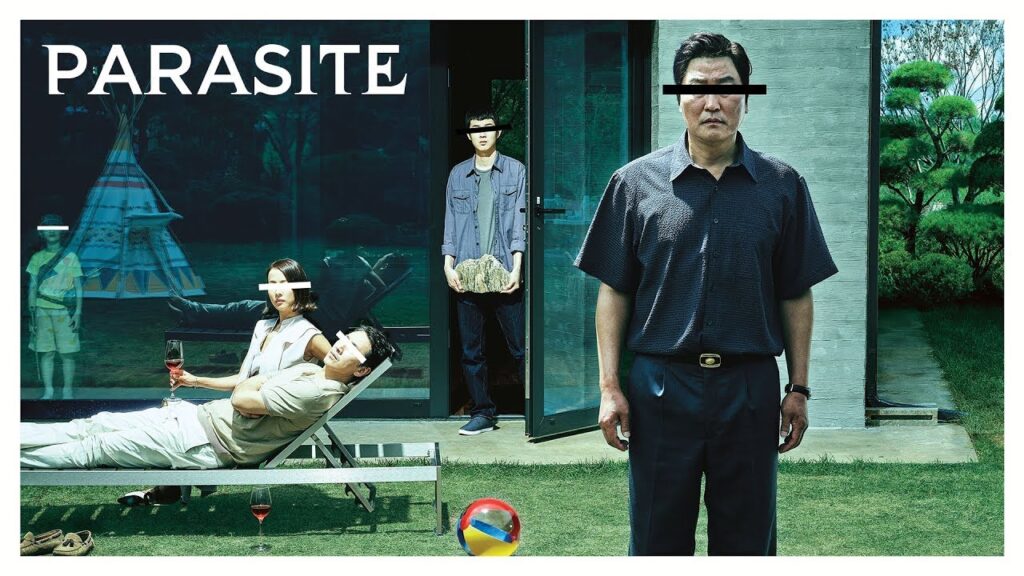

Parasite

Bong Joon-Ho (or Joon-Ho Bong…how do South Korean names work?) has been on my radar for years as the most promising director out of South Korea since Park Chan-Wook (Oldboy, The Handmaiden) and Kim Jee-Woon (A Tale of Two Sisters, A Bittersweet Life). Bong is a director who has yet to make a mediocre film. Barking Dogs Never Bite was a charming debut, Memories of Murder and Mother made a splash in the festival circuit, The Host is already a cult classic, Snowpiercer introduced Bong to American audiences, and Okja saw a modicum of success in the Netflix market.

Bong has always been a director of surreal excess – not in a Fellini kind of way, but in his use of over-the-top characters that feel divorced from our world (see Tilda Swinton in both Snowpiercer and Okja.) At the same time, his films always have a subtle narrative flair to them that elevates his subject matter in just about any context. For example, The Host is a traditional Godzilla-esque monster film, but its cinematography and characters prevent it from feeling stale and derivative. The sense of identity that Bong has created with such a short list of credits is definitely remarkable.

As such, Bong Joon-Ho offerings are something that I continually anticipate and crave. I need more Bong in my life. So, imagine my excitement when:

PARASITE WON THE FUCKING PALME D’OR AT CANNES

Yes, the Palme d’Or. Parasite now stands next to Pulp Fiction, Apocalypse Now, The Wages of Fear, and Taxi Driver as the recipient of the Cannes Film Festival’s most prestigious and unpredictable award. I’m not always a fan of the occasionally-random choices of the Cannes Jury, but regardless, the Palme d’Or is special, and has a tendency to predict which films will be revered critically in the future as pinnacles of cinema. Does Parasite really live up to all this hype?

HELL YES IT DOES!

Parasite merges Bong’s greatest strengths into one hilarious, heartbreaking, and beautiful package. It does the film a great disservice to pigeonhole it into a single genre, but essentially, Parasite is a dark comedy.

The film concerns a family of four – the Kims – who live in abject poverty in a filthy apartment in urban South Korea. They have no Wi-Fi or cellular service of their own (which the film very humorously points out is now a factor in one’s quality of life), and their residence is located inconveniently next to a bar, prompting patrons to frequently urinate on the family’s window. They’re all unable to find employment, and instead resort to elaborate, creatively-orchestrated scams to get by.

While the Kims are certainly poor, and the parents are negligent in many ways, it’s made abundantly clear that they aren’t unintelligent. The scams that the family pull off are wonderfully executed – these are no shell-game street cons. They engage in long, tedious, and meticulous preparation, even going so far as to compose and rehearse lines as if they were in a play.

The family’s son, Ki-Woo, is visited by a friend named Min. Min is about to study abroad, and has served as a tutor for the daughter of a wealthy family for quite some time. Min is in love with his student, and requests that Ki-Woo become her replacement tutor, in order to look out for her until Min returns to woo her when she is of age. He explains that Ki-Woo should have no problem weaseling his way in as a tutor, because of the mother of the family is rather “simple.” Ki-Woo agrees to this plan.

He meets with Choi, the mother of the family, and quickly manipulates his way into her good graces. Choi explains that her son, Da-Song, is an artistic prodigy, and in need of a tutor who can help him hone his skills. Ki-Woo informs her that he may know of someone who attended a prestigious school in Chicago that would be willing to help Da-Song. The person he is referring to doesn’t exist, but his sister Ki-Jung creates this character and commits to it, quickly becoming the fake prodigy’s tutor and psychiatrist.

The Kim family work together to orchestrate the untimely termination of the Park family’s housekeeper and driver, and Ki-Woo’s mother and father create their own characters to fit these roles. They slowly act their way into the lives of the Parks, and of course, a scenario like that can never end well.

I won’t identify where the plot goes from there, because this is just its central premise and I’d rather not ruin the film for you, but needless to say I was impressed. The themes explored through the juxtaposition of each family’s position in society are very on-point, and while the film had me in stitches throughout, it does not treat these themes without respect. When dealing with satire, it’s easy for the commentary to get lost in each attempt at humor, but Parasite side-steps this pitfall.

The film does a stellar job at introducing and developing each character, and this serves the plot nicely. It also has a great score, and the striking visual differences between the lives of the Parks and the living conditions of the Kims are dealt with in some creative ways. The camerawork is very competent, and successfully conveys the tension between the families as the grand charade unfolds.

There are some ways in which Parasite resembles “Ye Olde Screwball Comedy.” There’s slapstick humor sprinkled throughout, and the comedic pacing is brisk. For a dark comedy, the film doesn’t really head into, say, the kind of disturbing territory explored by The Handmaiden. The violence is both humorous and gruesome, but not overdone, and that’s actually refreshing. This could have easily reached borderline-torture-porn levels of violence, as many of this particular type of South Korean films do. Instead, there is some restraint in favor of character development and preserving the ability of the audience to take what’s happening on-screen seriously.

Parasite is easily one of the best films I’ve seen this year, and 2019 isn’t exactly devoid of quality entertainment. It’s also Bong Joon-Ho at the absolute height of his career, and that alone makes this worth seeing. Often, foreign films have a reputation for being more slow and methodical than American productions, but Parasite makes its two hours and change feel like 80 minutes, and by the time it ended, I wanted more. Parasite further cements Bong Joon-Ho’s reputation as one of the most notable directors of the 21st century, and it’s an absolute must-watch.

10/10

And remember…you don’t want to be like this woman:

So stop whining and deal with the subs. This is likely better than any American film you’ll see in 2019.